It is no secret to anyone that in recent times polarization has emerged as a typical feature of our society, at least in the West. The ideological and political extremes have been gaining strength, both in Europe, in the US, and in various Latin American countries, to the detriment of more centrist positions. Probably we are faced with a process that feeds on itself: the emergence of extreme right movements frightens the left, which reacts by mobilizing and radicalizing itself, and the same happens in the opposite direction. We enter, thus, in a dynamic where, to express it in a concise way, your radicality feeds mine. In the USA, Trump and his rhetoric encourages the emergence of an Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and at the same time Ocasio-Cortez’s rhetoric convinces Trump’s supporters that their leader is more necessary than ever. Or let’s think about it in Spanish terms: the movement for Catalan independence helps the extreme Spanish right wing of VOX to grow, and in turn the appearance and ascent of VOX helps, most probably, to increase the number of people in Catalonia who favor independence from Spain. Or in Colombian terms: the presence of the former FARC guerrillas in the Congress of the Republic encourages the most uncompromising sectors of the Uribist party, and the strenght of Uribism serves as an argument for the members of the FARC party to reaffirm their positions. The list of examples could follow. Your radicalism feeds mine.

In this brief article we do not wish to decide whether the proposals of one extreme are better than those of the opposite (each of the cases mentioned is different, and each has its own complexity, which should not be simplified). What we would like to examine is polarization itself, and the problems that it entails. What threats implies the growth of extremes to the detriment of the center?

First, an evidence: when most people gravitate towards the extremes, thinning the center, it becomes more difficult to reach agreements, pacts and alliances, and this tends to lead us to paralysis, stagnation and to the absence of solutions for the conflicts that plague us.

In the second place, it seems to us that the entrenchment of each other in their respective positions implies, often, an impoverishment of the intellectual landscape of society that experiences the polarization: surrounded by those who think like me and sitting light years away from the opposite position, I no longer have to strive to reason or clarify my views. Seconded by those who share my ideological space, and with hardly any contact with those who could question me and demand more precision in my proposals, it is very likely that they will become increasingly simplistic and less resistant to careful examination. At the same time, distance allows and encourages my adversaries to make a caricature of my ideas, and I of theirs. We are so far from each other that we only see a diffuse silhouette of the adversary: it is no longer possible for us to perceive the details and precise contours of their approaches.

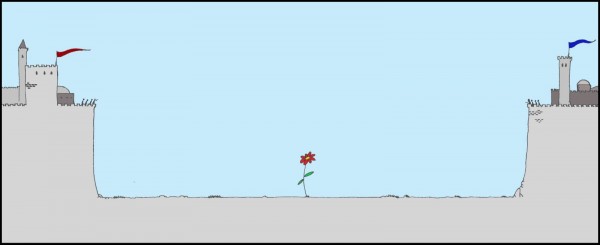

Let’s use an image to describe what is happening, or what could end up happening if the current trend towards polarization continues to advance: the image of two walled villages, two great fortresses within whose walls all citizens have taken refuge. No one lives outside these castles anymore. From the battlements of a fortress, the opposite fortress is barely visible, blurred and distant. Between the two is a large field. Empty. Unoccupied.

This image can help us weigh the most important issue: What impulses are behind the polarization? We dare to identify one (there are many more, but this one is key): the fear of ideological insecurity. Generally, we all want to be very sure of who we are, and to achieve this we must be quite sure of what we believe and what we deny. Ambiguity scares us. We need to know who is on our side. That is why extremes are attractive, because in them there is no longer uncertainty. The central field, on the other hand, irritates us by its ambivalence.

The problem with all of that is that, like it or not, reality is complex, full of nuances and contradictions. Therefore, the extreme may not be the best place to stand in order to try to understand the world. We already said it in a previous article: from an open field you can see the sky better than from the city’s main square. If we want to see the stars, we will have to leave the city.

We are not trying to judge negatively all radicalism, which is legitimate, and often necessary. The passion with which each one can defend his or her model of society, values and principles is not the issue. We are not advocating for undefinition or tepidity. We believe, however, that it is essential to practice an intelligent radicality: to adopt positions that, no matter how radical, do not allow themselves to be drawn into simplicity, do not give up the effort to understand the complexity of the century, do not crudely misrepresent the other extreme’s opinion and do not fear that territory, uncomfortable but fruitful, which is the ideological vacuum. The problem is not radicalism but intolerance, which, incidentally, is often born and fermented at the extremes.

If more people dare to occupy the uninhabited space that we are leaving between our walled cities we would discover that in it, and only in it, can agreements and the good political debate bear fruit: there it is possible to listen and respect the opinion of the adversary, and there it is possible to seek solutions for the common good. From there it will be possible to build a more just, more tolerant, more diverse society, where everyone fits. This debate will be impossible if we live locked in our castles. From its walls we can only, at most, shout some insult whose echo will barely arrive, if the wind is favorable, to the enemy walls. If what we want is to talk, we will have to leave the fortresses and approach those who do not share our views, to be able to hear them.