From Bolivia, Colombia, México, the Dominican Republic, Ethiopia, Spain and the US, the members of the Community of Saint Paul wish you a very blessed Christmas!

May the Prince of Peace be born in our hearts and in the entire world!

Merry christmas! Today we celebrate a unique birth: that of a child, vulnerable and defenseless, who came into this world in total anonymity, unknown to the powerful and important of the society of his time, and who, however, was also born marked by the promise of that would change the course of History, as the angel announced to the shepherds: "Do not be afraid. I bring you good news that will cause great joy for all the people. Today in the town of David a Savior has been born to you; he is the Messiah, the Lord. This will be a sign to you: You will find a baby wrapped in cloths and lying in a manger.” (Luke 2:10-12).

It was they, the irrelevant and poor shepherds, who were the first to visit him in the stable in which he had been born. If we think for a moment about that humble and simple place, which sheltered some involuntary pilgrims displaced by Roman power, we can affirm, without a doubt, that it smelled of sheep, since both the place and those who went to visit it would be impregnated with its smell. In fact, that was the first smell that surrounded the newborn, and that would remain engraved in his memory. Modern science affirms that olfactory memory is the most primitive and also the most emotional of the experiences that we accumulate as memories. A smell and a taste inevitably take us to a remote experience, recorded in our memory, and link us to it.

What do sheep smell like? Whoever knows the countryside, and the life of the shepherds, knows that the sheep smell of sweat and manure, that is, of poverty, and of humanity. The smell of it is not perfumed, nor does it convey the solemnity of incense or the sacred. What's more, he who gets too close to the sheep, and assumes responsibility for herding, not only ends up smelling like them, but also becomes filled with ticks, their inevitable parasites. In today's Feast we see how Jesus was born in a manger, in a stable, and thus he came to be impregnated with the smell that both animals give off, as well as the humanity that accompanies them, signified by shepherds. A penetrating smell that generates rejection, while defining a commitment to the poor and marginalized.

Nowadays, we can add, the sheep smell of drugs, migrants, and exclusion. It is the smell of those who fight to survive on the periphery of societies, and have been deprived of their dignity, as were the shepherds in the Christmas story. That is the first smell that Jesus knew. And it is the smell of Christmas. Pope Francis likes to ask shepherds to smell like sheep. Christmas teaches us that this smell was assumed from birth by the child we adore, a smell that forces closeness and solidarity with the suffering who multiply around us. It is only in this exchange with the sheep and their shepherds that we can come to understand the unexpected Savior who came to fully assume all of our humanity in order to share with us his divinity.

Today we celebrate the great feast of the birth of Jesus, the feast that, in a way, changes everything: the arrival of that child, and the good news that he announced, marked a turning point in the history of the human family. For believers, the feast of the incarnation means a profound transformation of the very idea of God: the haughty and distant God in whom we had believed, sometimes indifferent, other vengeful, always a judge, now comes to us in this poor and trembling baby, guarded only by his parents, humble and simple people, and an ox, and a cow. And that new identity of God, made one among us, is, indeed, an immense reason for joy.

One of the most endearing Christmas texts is the one we read, in preparation for today’s feast, on the fourth Sunday of Advent: the visitation of Mary, pregnant with Jesus, to Elizabeth, pregnant with John the Baptist. In this passage, Luke underlines precisely the joy that the presence of the child Jesus (in his mother’s womb) provokes around him: both Elizabeth and Mary herself are filled with joy, and the child John «leaps for joy» in Isabel’s belly.

Do we leap for joy when we feel close the presence of God?

It is a question worth asking. Because it is intriguing to observe that, often, the reaction that a closeness to the sacred provokes in us is not the reaction of John the Baptist—not one of joy, but of fear. Or guilt. Or both at the same time. Can we imagine Elizabeth saying to Mary, «When your greeting reached my ears, the child began to tremble with fear in my womb»? Or, «When your greeting reached my ears, the creature began to beat its chest, saying “through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault”»? And yet, that seems to be, sometimes, our response, when we feel the proximity of God.

These are perhaps understandable reactions. The divine is immeasurable: confronted with it, we become aware of our smallness, and, since we have been taught since childhood that God is a severe judge, then his closeness terrifies us. And our guilt seems more obvious to us, in his presence: this is what happened to Peter, that when he understood who Jesus was, and then exclaimed «Leave me, Lord, I am a sinful man» (Lk 5: 8).

And yet, these are reactions that respond to a pre-Christian idea of God—reactions that do not consider the Gospel. The fear and trembling that the sacred causes us is rooted in the experience of cultures that associated God with the terrible phenomena of nature, and that developed the idea of a God who, in any case, had to be appeased with our sacrifices. And all that has nothing to do with Jesus and his message; indeed, that is precisely what Jesus came to dismantle, with his good news that God is a merciful father, who loves us beyond comprehension.

To fully understand Christmas is to understand that the God in whom we, Christians, believe should always be, for us, a source of joy. Because Christmas means that God is not a judge, but a brother, who does not come to condemn us, but to walk with us, who does not look at us with disdain, but with tenderness, a God that we should not worry about appeasing, whom we should rather thank for all his goodness.

The question that we should then ask ourselves is whether with our behavior and attitudes we help to communicate that the closeness of God is comfort, and reason for happiness, or not. There is no doubt that sometimes, with our severity, with our rigidity and harshness, even with our bitterness, what we do is perpetuate the idea (this pre-Christian idea which contradicts the Gospels) that, before God, the most logical attitude is to be scared. When, in fact, the most natural thing would be to react like John the Baptist: leaping for joy.

A very blessed and merry Christmas to everyone!

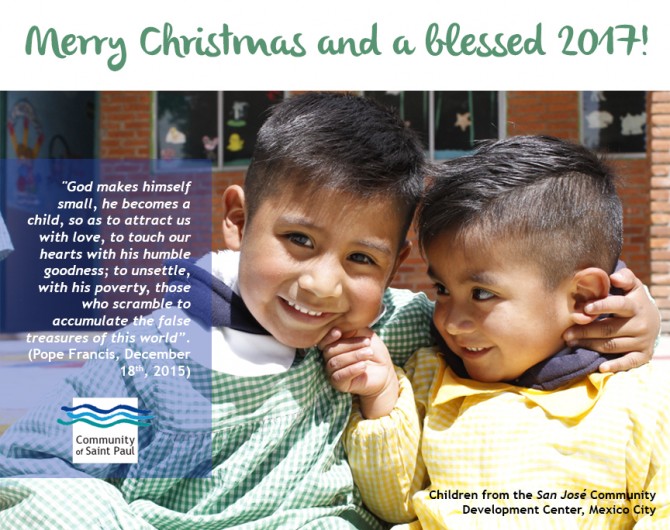

There is something inherently mushy about Christmas. And I think it is because anything to do with babies makes us soft and somehow vulnerable. And I think it is perfectly fine, normal, and even desirable. Many arguments can be made about how society has spoiled this important feast and how it has become another business opportunity. And yet, I still feel that it is OK to celebrate “mushiness” once in a while. It is OK to spend money to buy gifts for others; it’s OK to sing mushy songs constantly. It is a good reminder of how we are, or perhaps how we should be at times. The truth is that the sight of a child is unique. It has the capacity to soften our hearts, to instill in us feelings of compassion, happiness, joy, care, kindness, hope… Probably it brings in us the best of what we can become. Perhaps all these feelings are brought about because babies transmit a sense of frailty, an aura of innocence. When the baby is born, it is all we want the baby to be. A child fulfills all our expectation we have about him or her. We know a baby does not lie or deceive. A baby cannot hurt us in any way. So, on one side, there is the full confidence the child puts in us, and on the other side, we, in return, put all our confidence in the child.

Maybe all these feelings are the reason why Christmas has become so popular: because we all like to experience these feelings of innocence, kindness, and trust. We look forward to experiencing them as much as possible. So, let us celebrate Christmas as a constant reminder that we all have the capacity to be like babies and to treat others like babies, in a mushy way. Nowhere is written that to be an adult it means to be rude, insensitive, offensive, disrespectful or unkind, so…

Have a mushy Christmas!!!

We wish all our friends around the world a very blessed Christmas!

Not long ago I read the following verse from the poem The So Present Future, by Benjamín González Buelta:

I will no longer ask you when we will be numerous, but rather I will ask, “Where is, today, the manger of Bethlehem?”

I liked the idea of focusing on where the manger is today for us. Not where is success? Or where is the world evangelized? Or where is the church full? Or even where is there a happier world? Rather, where is—around us—a home filled with love. We may find it within our family, or with our spouse, or with our best friends: the manger of Bethlehem it is an intimate place that is pleasant, protected, full of affection, tenderness and honesty.

Once we have succeeded in recognizing where the manger of Bethlehem is for us, let’s begin to think which gifts are we going to bring to the manger. We are approaching the days when we all think about presents, and we could try to imitate the shepherds, who arrived at the manger with the simple presents that they could offer, and also those that were necessary at the moment.

One present could be a few days dedicated to our loved ones, or a dose of affection to someone in need, or a few pounds of dialogue, or some gallons of just having fun with a friend. And, why not give ourselves something, for we, too, are part of the manger? This gift could be some peaceful time, to just “be”, meditate, breathe and pray. An empty present, a present full of nothing—in order to detach ourselves from all that matters little and occupies much space and time. This Christmas, what gifts could be better than these, for our own manger in Bethlehem?

Christmas is a very popular feast, and there is no doubt that we are invited to celebrate it from its clearly Christian perspective, assimilating the more theological dimensions that it offers us.

One of these dimensions would be to see Christmas as a sign of communication: communication from a God who made Himself one in the midst of us, to transmit His message of salvation and love. In a society such as ours, in which communication advances faster and faster each day, and in which it seems that we are always connected, it’s good to reflect on how the feast of Christmas can help us.

God communicates Himself with tenderness: there is nothing more tender and fragile than a child. God doesn’t express Himself with violence, nor with big banners or billboards. He expresses himself with the sweetness of a newborn baby whose face is etched with traces of kindness, compassion and the love of His Father.

God communicates Himself with simplicity: “She gave birth to her first-born son and wrapped him in swaddling clothes and laid him in a manger”. Jesus’ birthplace is humble. In a society frequently drunk with consumerism and abundance, the feast of Christmas is a call to live what is important, to discover that the best gift we can receive is the company of our family and friends.

God communicates Himself with hope: “Do not be afraid. I come to proclaim good news to you, tidings of great joy to be shared by the whole people” say the angels to the shepherds. As worried as we may be with the problems of life, and as dark as we may view at times the social or ecclesial landscape, it is good that we allow ourselves to become filled with the happiness and the hope of today’s celebration. It is urgent that we Christians may proclaim, for ourselves, and for all willing to hear it, a message of joy, underscoring the blessings that come from God through the feast of the birth of His Son.

Let us allow the feast of Christmas to speak to us and help us improve our communication. That tenderness, simplicity and hope may help us communicate the joy of Christmas.

Martí Colom

Today, Christmas Day, we do not only remember the historical fact of Jesus’ birth, some two thousand years ago. We also celebrate that God— who with that birth wanted to come to meet us in a new way—is present in our world. Today we celebrate the feast of God’s closeness to us: God wants, as he wanted in Bethlehem, to be at our side, to accompany us, to be one of us, to encourage us, to comfort us, to help us, to give us a life of fullness.

And yet, in the beautiful reading of Luke which we heard at Midnight Mass (Luke 2:1-14) there is an intriguing phrase, which might almost seem like a minor detail with no importance —but it is not, and it deserves our attention: “While they were there the days of her confinement were completed. She gave birth to her first-born son and wrapped him in swaddling clothes and laid him in a manger, because there was no room for them in the inn.” There was no room for them in the inn.

Jesus was not born in a stable because Joseph and Mary loved oxen and donkeys, nor so that centuries later we could mount a beautiful manger in our houses every December, with its tiny houses, a river of aluminum foil, a little moss representing a meadow and the stable in the middle of everything. Jesus was born in a stable because no one wanted to open the doors of their house to his parents.

Amid the joy of this day, it is good to pay attention to this detail. And, since we are not only remembering a historical event of twenty centuries ago, but celebrating today’s living relationship of God with us, we must ask ourselves very seriously if we, too, sometimes do not close our doors to Christ.

We do it every time we send away a needy person without trying to respond to his need. And every time we exclude God from our thoughts and from our decision making. And when we turn a deaf ear to a demanding phrase of his gospel. And when someone with problems comes to us and we look the other way. And every time we evict God from our heart.

To truly celebrate Christmas is to say yes to the Lord’s coming, and to say that we really want to welcome the presence of Jesus in our lives. To truly celebrate Christmas, of course, also means that we are at ease with a God who becomes humble, fragile and small. To truly celebrate Christmas means that we renounce all arrogance, all dreams of greatness, and that we are at ease with a God who is Prince of Peace. And, to truly celebrate Christmas, as followers of the Prince of Peace, we renounce violence once and for all.

Let's celebrate, of course, the birth of Jesus! Understanding that, today, the idea is to welcome him into our inn.