If Catholics knew more about Judaism—its culture, feasts, and rituals—we would understand Jesus of the Gospels far more deeply, as He was born and died a Jew. The feast of Pentecost, which we have just celebrated, serves as a striking example. Pentecost was already one of the most important festivals in the Jewish calendar: the feast of Shavuot—which the Greek of the New Testament rendered as Pentecost, just meaning “fifty days later.”

The festival of Shavuot is one of the three major Jewish feasts, alongside Pesach (Passover) and Sukkot (the Feast of Tabernacles), during which pilgrims journeyed to the Temple in Jerusalem. This helps us understand why so many people from different regions of Israel and the Jewish diaspora could “hear” and comprehend the disciples who had just received the Spirit: "Parthians, Medes, and Elamites; inhabitants of Mesopotamia, Judea, and Cappadocia; people from Pontus and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt, and the parts of Libya bordering Cyrene; visitors from Rome, both Jews and converts; Cretans and Arabs—we hear them speaking in our own tongues of the mighty works of God!" (Acts 2:9-11).

Shavuot was originally a festival celebrating the first fruits of the harvest, the Bikkurim, but above all, it commemorates the moment when God gave the Law to Moses and, by extension, to the people journeying through the wilderness. For the Jewish people, it marks the giving of the Law, whereas for us Christians—God’s pilgrim people—it marks the giving of the Spirit. To embrace this reality (Law-Spirit) not as a contradiction or establishing a superiority, but as a creative tension, would be truly fruitful.

Another way in which understanding Shavuot can illuminate Christian Pentecost is that Shavuot not only recalls the historical event but also invites the Jewish people to renew their commitment to the Torah and a life guided by divine wisdom. Similarly, Christians commemorate the historical event of Pentecost, but it also holds a petition: that the Holy Spirit of Jesus, the Spirit of God, may continue to be poured out upon us and our communities. We ought to be individuals and communities in a permanent state of Pentecost.

In Shavuot, the first fruits—bikkurim—of the harvest were offered in the Temple. Saint Paul takes up this image when he speaks of the "first fruits of the Spirit": "And not only that, but we ourselves, who have the first fruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly as we wait for adoption, the redemption of our bodies" (Romans 8:23). Just as Shavuot marked the offering of the earth's first fruits, Pentecost grants us the first fruits of the Spirit—a foretaste of future fulfillment and the promise of the coming Kingdom of God.

The Holy Spirit, poured out at Pentecost, is not merely a gift of the past but an active presence that transforms Christian life into fertile ground. Much like the bikkurim, which were a sign of hope and gratitude—a tangible assurance that the harvest was on its way, but already initiated—the first fruits of the Spirit place us in another beautiful tension: we have already received, and yet, we still await.

This experience is translated into concrete fruits: love that forgives, peace amid chaos, fidelity that defies time. Hope against all evidence. Each of these fruits, though invisible and real, is part of that initial harvest that prefigures the fullness of the Kingdom. It is no coincidence that Saint Paul also speaks of the "fruit of the Spirit" (Galatians 5:22): what began as an agricultural image becomes an embodied spiritual reality.

Pentecost is not merely the remembrance of a received gift but the thrust of an entrusted mission. Just as the first fruits were joyfully brought to the Temple as a sign of gratitude and hope, now the Church—animated by the first fruits of the Spirit—becomes a living offering for the world. Each disciple, filled with the Spirit, is sent forth as a sower of new life: where there is division, we bring communion; where there is darkness, we kindle hope; where there is death, we proclaim the Resurrection.

Christian life, then, is a journey of mission—proclaiming the arrival of a Kingdom that not only is coming but is already fermenting among us. We are a Church in exodus, moving forward, called to leaven history with the yeast of the Kingdom—not passively awaiting its future fulfillment, but anticipating, announcing, and embodying it.

There is a revealing factor in the metaphor for Pentecost. At his coming, the Holy Spirit fills the house with noise and wind. It then divides itself in tongues of fire descending on those gathered. This double movement resolves a dangerous dichotomy, namely, whether the Holy Spirit is a communitarian and global reality or a personal and individual experience.

There is no doubt that the experience of the Holy Spirit is a call to inner motivation, to the tireless search for enthusiasm and to go out to meet those who are different, those who speak a different “language” than ours. This is the movement of the Holy Spirit descending into each of us. The Holy Spirit has to touch our hearts.

But declaring oneself individually as “filled with the Spirit”, as opposed to all those who do not have it, it is a dangerous claim—one that easily leads to intolerance and arrogance. The indispensable requirement for the arrival of the Spirit is to be “gathered” together. First, the Spirit engulfs the house and only then descends on each of the disciples.

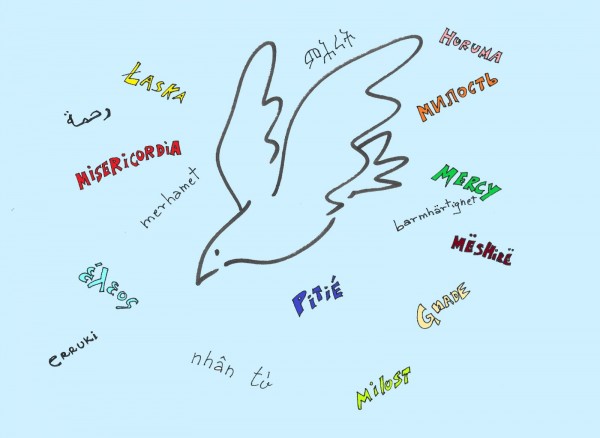

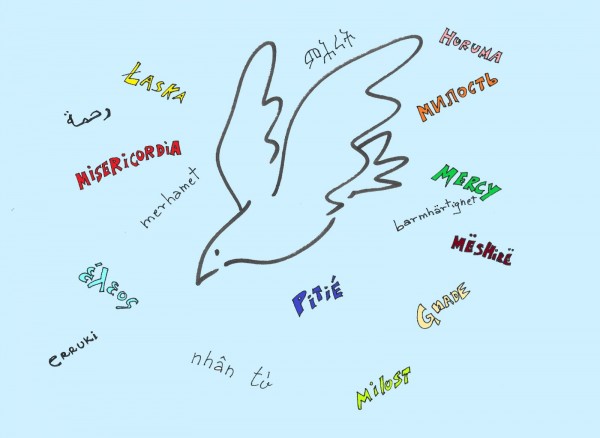

The Holy Spirit is a collective experience of the whole Church, and even outside of it. Pentecost is a communal feast. It calls for a personal commitment, but one that compels us to be an open Church. To be open to those who are not like us. The Spirit transforms the Church, so that it is her who wishes to be understood by others. She is not waiting for others to do the effort to adapt to her language. She rather strives to speak in the languages of the world.

The Holy Spirit breaks into the Church, and fills it all, and then inspires each one of us to open up to become closer to all, to make ourselves neighbors of others and thus become witnesses of Jesus’ love.

This past Sunday we have celebrated the great feast of Pentecost. In the passage from the book of the Acts of the Apostles that narrates the descent of the Holy Spirit on the gathered community (Acts 2:1-11), it is clear that the spirit comes to transform reality. If before it is poured out on the disciples they are a frightened, inward looking group, after receiving it they are a courageous community that projects itself to the world.

If, beyond this fundamental observation, we look at what their preaching produces, we see that the fruit of the Spirit having been poured out on the community is that the Gospel («the mighty acts of God») is proclaimed in a way that everyone can understand it.

The task of the Church, from the day of Pentecost onward, is to translate the Christian message so that peoples of all ages and cultures can understand it. In the same way that the passage from Acts makes it very clear that people of diverse origins («Parthians, Medes, and Elamites, inhabitants of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia»…) heard the preaching «each in our own tongue», today we must strive to make the Gospel comprehensible to all.

We will not be carrying out our mission if we speak an opaque language, far removed from the language of the street, no matter how erudite it may be and no matter how elaborate our arguments are —in our opinion. In this case, we will have lost sight of the fact that the mission was, and always will be, to translate: to translate the meaning of the life and the words of Jesus for each new generation, for each new culture, for each person.

Today, in the midst of a rapidly changing society in which cultural categories that we used yesterday are no longer understood, perhaps it is more urgent than ever to know how to translate our message. Assuming that the very language, the expressions and the images that helped us to get closer to Jesus may no longer work for those who ask about him today.

Let us ask the Holy Spirit, this Great Translator, to inspire us with new and necessary ways to express our deepest convictions.

In the story of Pentecost that Luke offers us in the book of the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 2: 1-11), the absolute liberality with which the Holy Spirit pours itself over the disciples is striking. Over all the disciples. The Spirit is indeed abundant and splendid. The text states that the tongues of fire “rested on each of them” (that is, without avoiding or eluding anyone), and then it insists: “All of them were filled with the Holy Spirit.”

The Spirit is not stingy, it is not selective, and it is not elitist. The Spirit ignores hierarchies, teaching us, incidentally, that they are always a human construction.

Let's imagine, for a moment, an alternative text:

“On the day of Pentecost, they were all together in one place. And suddenly from heaven there came a sound like the rush of a violent wind, and it filled the entire house where they were sitting. Divided tongues, as of fire, appeared and began to flutter above the disciples looking for the most capable, those who were in command of the group, the smartest, the best, and then settled on them. The three or four lucky ones were filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in foreign languages, while the others congratulated them, a little disappointed and secretly envious, because they had not been worthy of receiving a tongue of fire.”

This fictional text, which Luke did not write, would tell us about a Spirit that would reconfirm human hierarchies and which would only be given, with much caution, to a few; perhaps to those who would have shown that they would use well the gift received.

And yet, this is not the text that Luke left us. In his, in the authentic, the tongues of fire rest on each and every one of those present, and the Spirit inspires all of them, without exception. We can guess that there were brave disciples and fearful disciples in that room; men and women; young and old; smart disciples and others less brilliant; talkative and reserved; audacious and hesitant; vigorous and tired ... as in any human group. And the Spirit came to all, and all were filled with it.

Our human categories (those with which we look at each other, assessing the successes of some and underlining the mistakes of others, applauding achievements and pointing out failures, looking for skills and marginalizing those we suspect are plagued by defects) should never obscure the fact of that, on Pentecost, the Spirit was not deceived by any elitism of this sort, nor by any hierarchy, and was given, with confidence and freely, to all those who were gathered.

It is startling, in fact, that a Church that was born in such a way ended up so concerned, in her later history, about establishing a strongly hierarchical model, thus imitating the vast majority of human institutions. This is a fact that speaks more about our resistances to the breath of the Spirit than of our docile adherence to its impulse. It would even seem that, at times, the Church has tried to reflect something similar to the fictional text that we have imagined instead of trying to live the reality of the authentic text.

The community desired by the Spirit, in short, is not one in which a few are granted the right to speak in the name of God, while others have to keep silent, listening and agreeing. The Church that is born in Pentecost is the one that celebrates that the Spirit of God has rested on each of its members, without discriminating against anyone, inspiring them all. It is the community in which “all of them began to speak in other languages, as the Spirit gave them ability.” It is the Church that celebrates with joy the audacious generosity of God.

As is well known, the word "Pentecost" comes from the Greek and means the fiftieth day. The number 50 is, for the Jews, a symbol of fullness: a week of weeks (seven by seven, plus one). This feast, which originally had an agricultural character, is celebrated fifty days after the Jewish Passover. It is thought that fifty days after the exodus from Egypt, the people of Israel sealed the covenant with Yahweh on Mount Sinai under the guidance of Moses.

Today, seven weeks after Jesus’ resurrection, Christians celebrate the outpouring of the Spirit to the apostolic community, not as an independent feast, but as the culmination of Easter: "Receive the Holy Spirit!"

In the midst of the bustle of people of different tongues who came to Jerusalem to celebrate the Jewish Pentecost, the Holy Spirit gave the apostles the strength to communicate Jesus’ message of love to all. After the departure of the Lord, confusion and dispersion could have triumphed, but the Holy Spirit inspired the community of disciples to work for the common good and to share the message of unity with all the nations. In this way the Risen One reaches the ends of the earth.

In a society as polarized and fragmented as ours is, we need to live celebrating Pentecost. We ask for the presence of the Holy Spirit, and we can say:

Come Holy Spirit, teach us to dialogue as brothers and sisters.

Come Holy Spirit, help us to understand the language of the adversary.

Come Holy Spirit, teach us to discover that we are all brothers and sisters.

Come Holy Spirit, free us from the threat of turning our countries into a new Babel, incapable of building a future of fraternity.

Come Holy Spirit, and free us from intolerance, from stubbornness, which increasingly distances us from all effective collaboration.

May we repeat among ourselves those words of Paul to the first Christian communities: "Do not stifle the Spirit" (1Thes 5,19). Let us not weaken our faith in the Father of all, and let us not quench our hope for a more fraternal society.