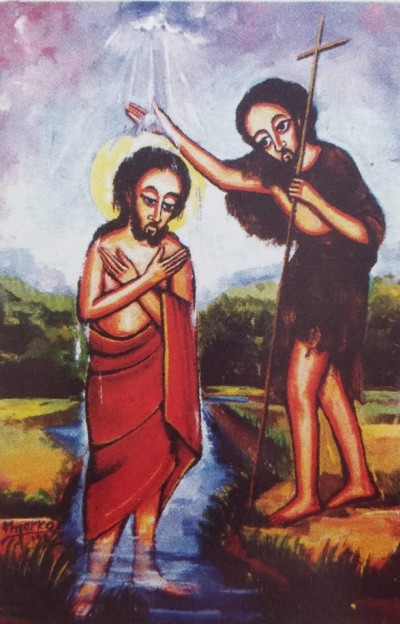

The Baptism of Jesus is one of the most important events in his life. However it is a feast, a week after Epiphany, that merely tiptoes through Christmas the celebrations, becoming perhaps one of the most depreciated and less valued celebrations of the liturgical calendar.

It could be seen as just another episode, when in fact it was perhaps the fundamental event of his life, the moment in which Christ assumed his mission and began his public ministry, most probably still without knowing the scope and significance of his decision. Popular culture makes us believe, however, that very early in His life, almost at birth, Jesus would be endowed with the capacity to be all knowing as to the events during his life. Thus, he knew in advance that he was going to be baptized by John at the River Jordan, and his mission and identity. If this is our understanding of Jesus’ self-perception, then his baptism loses its significance.

Deep down, there is a need to believe that in Jesus’ baptism there was not a rational and conscious decision but that is was somehow predetermined. To believe that Jesus didn’t have a choice, thus having doubts during his life before and after his baptism, comes from the fear of compromising his divinity making him too much like one of us. This is why, despite the fact of his humble and simple birth, we have made him a superman, endowed with superhuman powers, in this case, the power of omniscience even at his birth. The problem is that in the effort to avoid compromising Jesus’ divinity we run the risk of questioning his full humanity.

We should be careful with the superhuman characteristics that we often ascribe to Jesus to protect his divinity. In fact, the more special and super-human we make Him, the less human he becomes. In this process of "super-manning" Jesus we lose the key and transcendental element of the Incarnation and therefore of our faith: Jesus is a person like all of us, no less and no more.

True, he is also God, but the divinity of Jesus does not come from alleged super-human attributes but by his ability to be fully open to the will of the Father, by his radical capacity to love and give himself to others. This is the greatest paradox of our faith, of the faith in God made man: The more human we are, the freer we are to love, and—in a way—the more divine we become.

In sum, if in this longing to make Jesus super-human, we believe that from an early age he knew about his messianic role, his life and his fateful end, then his baptism is obviously irrelevant.

The experience of Jesus in the Jordan is not just another episode preset and known to him; it is the fundamental experience of his life. At his baptism, Jesus makes the decision to dedicate his life for the liberation of others and he recognizes himself as the Messiah. The crucial part of the baptism is that Jesus is able to change the traditional messianic expectation characterized as a victorious, powerful, exclusivist, political and religious Messiah to a universal Messiah centered on the poor and based on compassion and tolerance, not only political but for the integral liberation of the person as a historical, social, religious, cultural and psychological subject.

From the time of his baptism, through the call to his disciples and throughout his public ministry, Jesus’ mission is just trying to convey to others and to us what kind of Messiah he is and how we can imitate him. At the end, the attempt will cost him his life but will also enable us to follow him.