Not long ago I read the following verse from the poem The So Present Future, by Benjamín González Buelta:

I will no longer ask you when we will be numerous, but rather I will ask, “Where is, today, the manger of Bethlehem?”

I liked the idea of focusing on where the manger is today for us. Not where is success? Or where is the world evangelized? Or where is the church full? Or even where is there a happier world? Rather, where is—around us—a home filled with love. We may find it within our family, or with our spouse, or with our best friends: the manger of Bethlehem it is an intimate place that is pleasant, protected, full of affection, tenderness and honesty.

Once we have succeeded in recognizing where the manger of Bethlehem is for us, let’s begin to think which gifts are we going to bring to the manger. We are approaching the days when we all think about presents, and we could try to imitate the shepherds, who arrived at the manger with the simple presents that they could offer, and also those that were necessary at the moment.

One present could be a few days dedicated to our loved ones, or a dose of affection to someone in need, or a few pounds of dialogue, or some gallons of just having fun with a friend. And, why not give ourselves something, for we, too, are part of the manger? This gift could be some peaceful time, to just “be”, meditate, breathe and pray. An empty present, a present full of nothing—in order to detach ourselves from all that matters little and occupies much space and time. This Christmas, what gifts could be better than these, for our own manger in Bethlehem?

Today Advent begins in the liturgical calendar of the Church: four weeks that are usually described as a time of waiting, a time during which we pause and prepare for the feast of the birth of Jesus.

Someone might ask: Is Advent really necessary? If what’s important is what comes next— Christmas—could we not skip the preamble? Here we would like to emphasize that Advent, this lesser liturgical time (which perhaps does not have the heft of the Christmas season that follows it, or Lent, or Easter) offers an invitation that is especially pertinent for today, one that we would do well to attend. Advent points to the importance of being able to wait, and it would not be an exaggeration to say that we are currently losing the ability to do such a thing, to do it well, and that with this, we are missing the benefits of waiting.

Today we are becoming increasingly unable to wait: we want everything instantly. We live in a world that regards immediacy as an indisputable value. All forms of waiting, therefore, are a nuisance that must be eliminated. We purchase what we need online, so that we do not have to wait to be served at the counter of a store. We download films from digital platforms and watch them in our living room, so as not to have to line up at a theater, wait for everyone to be seated, and for the trailers to finish. We read the news on our phones because it irritates us to wait for the newspapers to arrive at our kiosk or for the time when the television news airs. So as not to waste time waiting for the food to be cooked, we call a delivery service, which in the shortest possible time appears on our doorstep with pizza or whatever we have ordered, hot and ready to be consumed. The so-called "waiting rooms" (the doctor’s, the lawyer’s) are for many people a relic of the past, and when they cannot be avoided, we endure them as if they were real torture chambers! Indeed, we do not find any value in waiting.

And yet, there is something unnatural in our desire to accelerate the results we long for, because many of the essential things in life continue to require, whether we like it or not, patience and the ability to wait. The gestation of a baby in her mother's womb lasts nine months. The ripening of a fruit on the branch of the tree takes weeks. Weaving a friendship can take years, just like studying for a career, learning to master the art of playing an instrument or knowing how to express ourselves in a new language. Savoring a good book may require many hours of slow immersion in its pages, and there are poets who have spent decades retouching and remaking the same poem. It took Michelangelo more than four years to paint the Sistine Chapel, Tolstoy needed five to write War and Peace, the construction of the Taj Mahal lasted 22 years, and 136 years ago they began to build “La Sagrada Familia” church in Barcelona, and it is still unfinished!

It is likely that the modern cult of immediacy is turning us into more efficient people who do more things in less time, but perhaps also more coarse people, because doing things well requires patience, dedication, and a willingness to discover the slow rhythms of nature. And yes, to know how to wait, and even more, to savor the waiting as that which will make us enjoy and value the attainment of what we have hoped for, with patience. Indeed: the great danger of obtaining everything (or almost everything!) in a second by pressing a key on our telephone or computer, is that we can lose the ability to distinguish art from garbage, truth from lies, the deep from the superficial, an authentic love from a passing friendship. Garbage, lies, superficial stuff and passing friendships can be produced in an instant, without effort; on the other hand, art, truth, depth and authentic love cost, they need time to be formed, like the body of a child in the womb of its mother, like a tree that takes decades to grow, like a masterpiece, like trust, like sincerity.

Advent, in short, sends us a warning: "Do not despise the art of waiting." It is an essential warning, and that is why we truly need this season that begins today.

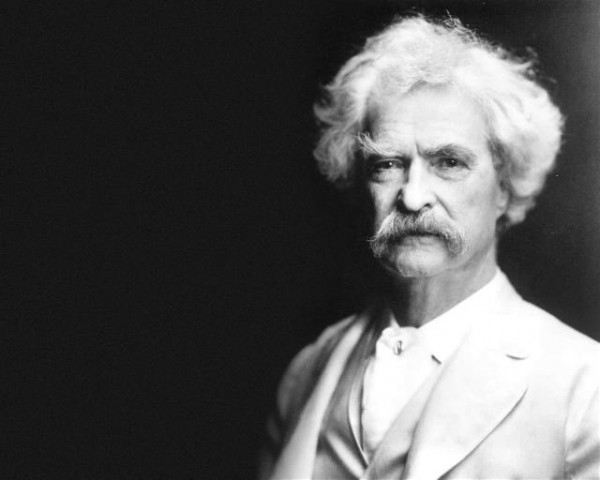

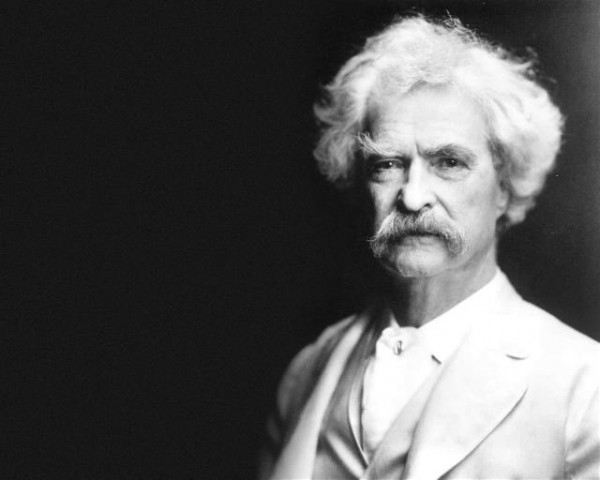

“Post-truth”, Mark Twain and our fears

Apparently, we live in a world that values truth. If we were asked what virtues we expect to find in our political leaders—and in intellectuals, scholars, artists, journalists, etc.—surely many of us would mention integrity and honesty, without having to think too much about it. We want to believe that our society applauds those who tell the truth and repudiates those who lie.

However, is that so? To what extent do we really care about the truthfulness of the politicians we vote for, the analysts we listen to, and the authors we read?

It is pertinent to ask ourselves these questions because, in fact, the evidence suggests that the current public debate is filled with lies and liars. Political leaders of every stripe place themselves daily in front of microphones and without much hesitation tell us half-truths, distort facts, omit information, and declare things that they do not know. So much so that we have even coined a term, the euphemistic "post-truth," to speak of this phenomenon.

But perhaps this is not the main issue at stake: there have always been characters who thought that deception was the fastest way to power. The question that we would like to explore is a different one: we want to ask ourselves to what extent we live in the post-truth era because we— ordinary citizens— allow it. Why do we allow them to lie to us?

The problem, indeed, may be not so much the leaders who offer a discourse in which reality is distorted, but the population that applauds them despite their lies. Perhaps what happens is that (contrary to what we say to ourselves) we do not seek, above all, leaders whose commitment to the truth is unquestionable. Perhaps what we look for in our leaders are other things, and we are more than willing to renounce truth if this is the price to pay to obtain these “other things.”

The normalization of lying

We do not want to deny the existence of current leaders committed to the truth, but let us just say, as a starting point, that falsehood is not strange, not even exceptional, in the mouths of public figures that appear daily on our screens and in our newspapers. It is a global phenomenon: in the north and in the south, in large countries and in small nations, in democracies and in dictatorships, there are authorities who lie, and who lie blatantly. It is so common that it no longer shocks anyone.

Fortunately, there is no lack of more or less independent media that insist on highlighting the lack of integrity of public figures. It is already common, for instance, for the press to analyze the veracity of the statements of the participants in an electoral debate, once the debate has concluded. They inform us: "Candidate 1 distorted the reality in this statement; candidate 2 has no factual evidence to support what he said in response to candidate 3; the economic figures offered by candidate 3 are questionable.” They inform us, and nothing happens. This is the issue.

The real problem, we insist, is not that there are politicians who lie: the most serious matter is that the exercises to unmask their lies do not negatively affect their careers. The most serious matter is that they lie, we know it and nevertheless, we continue to vote for them, as if we did not care that men and women who are asking for our vote, or who already direct our governments, drop, here and there, inaccuracies, lies and slander. It seems, as we pointed out, that we have accepted that in the political game lies are inevitable.

Never let facts get in the way of a good story

Perhaps there is some truth in the idea that lies cannot be avoided, because the falsehood in which our leaders so easily fall is, in part, a consequence of the age in which we live. In our digitalized, accelerated and hyperconnected world, where nobody seems to have time to stop to examine the complexity of things, only simple messages work well. Our leaders have understood that their discourses must be direct, devoid of nuance, and they are forced to simplify very complex realities. Many times, therefore, the lie does not start as such: it starts as an attempt to reduce complicated problems to outlines that are easy to explain. To achieve this, one day an element of the problem is ignored ("there is no time to get into that today"); another day the aspect of the issue that we wish to highlight is magnified ("everything else is secondary"); another day the statement of an adversary is taken out of context; and very soon, after taking several steps in this direction (simplify, simplify, simplify) what is being communicated is nothing but a lie.

It would seem, in short, that our leaders have decided to follow the ironic saying attributed to Mark Twain: "Do not let the facts get in the way of a good story." The facts are a bother for those who seek the applause of a society that never has time to examine any issue calmly. That is what many understood, and it seems that more than one or two have turned the "advice" of Tom Sawyer’s author into their most sacred rule. With a tweet it is easier to explain a good story in black and white than to describe the gray tones and ambiguities of life. Of course, to make our history a good one, we will have to exclude uncomfortable and contradictory facts. Many politicians, invested in this logic, cease to be careful analysts of reality to become excellent storytellers: what matters is no longer rigorously examining the totality of the available data, its paradoxes and its ambivalences; what matters is to develop a coherent and attractive narrative that everyone can understand. Even if to achieve this we must discard some facts (those that would spoil the clarity of the story).

Mark Twain ironically described the mechanism of what today we call “post-truth”

We live immersed in a gigantic global information market. In this market, where the supply of messages is vast, those who believe they have something to say compete with each other tooth and nail to get the attention of a significant number of recipients. The struggle is unleashed to make sure that “my” message is heard by more people than yours; the fight is fierce to ensure that my opinion does not disappear in a few seconds, overwhelmed by the constant flood of other people's opinions. In this fight to get even some brief moments of relevance, the simple messages (the "good stories" that, to be so, must ignore the facts that would spoil them) are much more likely to survive than complex, nuanced messages. To say it somewhat harshly: if you want to be heard, lie.

Why do we allow them to lie to us?

What has been said so far may explain why the commitment of so many public figures to the truth is, at best, tenuous. Our leaders look for relevance, they are terrified to be thrown out of the spotlight, and they think that if they simplify their messages (and sooner or later that leads them to lie) they will be able to remain relevant. Yet, why does the tactic work? In other words, the question that remains to be answered is the one we asked ourselves at the beginning of this reflection: Why do we continue to vote for, listen to and applaud people who falsify the truth? Why do not we reject the liar? Why do we allow them to lie to us?

Although it is probable that there is no universal answer to this question, to think in the following direction seems interesting to us: perhaps we tolerate being lied to because we crave a home. We long with all our heart to have an ideological house, a community of thought and sensibilities that we may call "home" in which we may feel comfortable and safe. We want well-defined maps of the moral territory in which we move, and we want to recognize who is on our side. We need to know with whom we are family. This longing has a correlative fear: the terror of living without a home, of not having a side, of being what we might call "ideologically homeless.” It is this fear, combined with that longing, that leads us to tolerate the distortions of our leaders. In reality, what we expect from them is not a truthful and factually irreproachable discourse but a message that confirms our beliefs, certifying that we are on the right side, a message that ratifies our sensibilities, that corroborates what we already know. We do not want to question our leaders when they say half-truths or when they lie without blushing, because questioning them would push us to the periphery of the group and, from there, perhaps, to indigence and to becoming those ideological homeless we dread.

In short, we tolerate the lies of our leaders because they are ours. We let them lie because what matters is that they offer us the ideological house we long for.

Is it possible to correct this logic and recover the centrality of truth, so that facts can help us better understand the world in which we live and seek lasting solutions to our conflicts? We think so. To achieve this, the main thing for us to do is to lose the fear of living without a home, and to understand, somehow, that it is easier to see the stars from a clearing in the middle of the forest than from downtown. Freed from the fear of being left without an ideological house, we can dare to be a bit more critical of our leaders; we can dare to recognize what is reasonable in the position of our rivals; we can run the risk of examining the paradoxes, complexities and contradictions of each situation. And, we can stop sacrificing the facts in order to obtain a good story. Better yet: at last we will understand that the best story is the one that does not exclude any facts. Mark Twain, deep down, knew it very well.

In the story of Pentecost that Luke offers us in the book of the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 2: 1-11), the absolute liberality with which the Holy Spirit pours itself over the disciples is striking. Over all the disciples. The Spirit is indeed abundant and splendid. The text states that the tongues of fire “rested on each of them” (that is, without avoiding or eluding anyone), and then it insists: “All of them were filled with the Holy Spirit.”

The Spirit is not stingy, it is not selective, and it is not elitist. The Spirit ignores hierarchies, teaching us, incidentally, that they are always a human construction.

Let's imagine, for a moment, an alternative text:

“On the day of Pentecost, they were all together in one place. And suddenly from heaven there came a sound like the rush of a violent wind, and it filled the entire house where they were sitting. Divided tongues, as of fire, appeared and began to flutter above the disciples looking for the most capable, those who were in command of the group, the smartest, the best, and then settled on them. The three or four lucky ones were filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in foreign languages, while the others congratulated them, a little disappointed and secretly envious, because they had not been worthy of receiving a tongue of fire.”

This fictional text, which Luke did not write, would tell us about a Spirit that would reconfirm human hierarchies and which would only be given, with much caution, to a few; perhaps to those who would have shown that they would use well the gift received.

And yet, this is not the text that Luke left us. In his, in the authentic, the tongues of fire rest on each and every one of those present, and the Spirit inspires all of them, without exception. We can guess that there were brave disciples and fearful disciples in that room; men and women; young and old; smart disciples and others less brilliant; talkative and reserved; audacious and hesitant; vigorous and tired ... as in any human group. And the Spirit came to all, and all were filled with it.

Our human categories (those with which we look at each other, assessing the successes of some and underlining the mistakes of others, applauding achievements and pointing out failures, looking for skills and marginalizing those we suspect are plagued by defects) should never obscure the fact of that, on Pentecost, the Spirit was not deceived by any elitism of this sort, nor by any hierarchy, and was given, with confidence and freely, to all those who were gathered.

It is startling, in fact, that a Church that was born in such a way ended up so concerned, in her later history, about establishing a strongly hierarchical model, thus imitating the vast majority of human institutions. This is a fact that speaks more about our resistances to the breath of the Spirit than of our docile adherence to its impulse. It would even seem that, at times, the Church has tried to reflect something similar to the fictional text that we have imagined instead of trying to live the reality of the authentic text.

The community desired by the Spirit, in short, is not one in which a few are granted the right to speak in the name of God, while others have to keep silent, listening and agreeing. The Church that is born in Pentecost is the one that celebrates that the Spirit of God has rested on each of its members, without discriminating against anyone, inspiring them all. It is the community in which “all of them began to speak in other languages, as the Spirit gave them ability.” It is the Church that celebrates with joy the audacious generosity of God.

There is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in.

Leonard Cohen (Anthem)

Traditionally our faith as believers and Christians, specially within the Catholic tradition, is defined and understood as a collective event. The Church, the community, the sacraments are indicators of the importance of the collective character of our faith. Even the hermit has a collective faith: the “Robinson Crusoes of faith” do not exist.

However, when we talk about the resurrection, we tend to strip the faith of its social content and we retreat to a more intimate dimension; the Resurrection seems to be confined to a personal dimension, an individual event inaugurated by Jesus. Beyond theological considerations, the following is a reflection on the meaning of the resurrection from a collective point of view. The purpose of these lines is extremely modest: to see how at a sociological level there is an association between death and resurrection, and to look at what is, then, the meaning of the latest.

Jesus’ passion was not only one man’s torture, it was not only the indescribable physical and psychological pain of dying on the cross. The unbearable torment of the cross was also a dramatic collective event. The crucified Jesus was a tragedy with deep social implications. It was precisely from this collective debacle that the nascent, frightened and weak Christian community began to live the experience of the resurrection, to gain awareness, courage, strength, and conviction; It was there that the cross became not only an instrument of torture but a symbol of life, a sign of a common struggle. The passion as a social phenomenon is somehow necessary for the resurrection of a people or a community.

In the same way that Jesus made the Passover from death to the life, analogically we can observe how oftentimes a reprehensible and unjustifiable act of violence or a social injustice are capable of bring about new life.

We don't have to look very far to find some dramatic examples of this: last February 14, we witnessed a shooting in a USA school, another tragedy to add to the heartbreaking statistic of gun victims in the country. That awful event has started a popular student movement to demand changes in the regulation of the acquisition and possession of weapons.

Another example is the recent announcement by Pope Francis about the canonization of bishop Oscar Romero of El Salvador, murdered on March 24, 1980 while celebrating the Eucharist. His death helped the growth of popular movements against political and military tyrannies across South America, and elsewhere.

Still going back in time, another example was the horrific killing of a young Emmett Till in 1955, in the State of Mississippi. From the pain and rage of this racially motivated crime, African Americans responded with new strength through the Civil Rights movement in the USA.

Only five years later, in the Dominican Republic, the Mirabal sisters, three women who dared to confront the tyranny of Trujillo’s regime, were killed: it was November 25th, 1960. To honor them, that date was later chosen to celebrate the International Day for the elimination of Violence Against Women, and since then there is a growing awareness about women’s abuse, becoming, 50 years later, one of the basic demands for women’s right.

More examples could be added of people who have led to a collective resurrection through their own passion and sacrifice, such as Mahatma Gandhi, with his non-violent struggle for India’s independence and peaceful co-existence between Hindus and Muslims, or Harvey Milk, assassinated in 1978 for his political activism defending the rights of homosexuals in San Francisco. These are well known examples. There are many anonymous passions, only known and experienced at the local level, or within a group or even in a family. But in any case, they still bring about the mobilization of that group.

All these passions, regardless of how well-known they are, raise the conscience of a group or a community. It’s a jolt that wakes up sleeping consciousness, shakes up apathy and takes us out of our comfort zone, and moves us to political or social action (the resurrection). It does not need to be revolutionary or violent. The collective being moves slowly, but the initial spark, the initial movement, it’s almost always traumatic (a passion).

All collective passions, like Jesus’, dramatically reveal the cracks of the social structures, that are often hard with the weak and accommodating with the strong. But through these passions, in turn, there is always the possibility for a new resurrection, a movement of light, of hope and change. The Resurrection of Jesus is a permanent invitation to us to turn social injustice, exclusion and intolerance into life, hope and social integration.

Already in the midst of Holy Week, tonight we begin the Triduum with the celebration of Holy Thursday, the Evening Mass of the Lord’s Supper. There are many ways to approach Holy Week and the Triduum. One of them is considering the different locations, or scenarios in which the Passion takes place. We read the text of the Passion twice during Holy Week: We read the synoptic version on Palm Sunday (Mark, Matthew and Luke) following the annual cycles of the Lectionary (this year we are reading Mark) and John’s version, which we read every year on Good Friday.

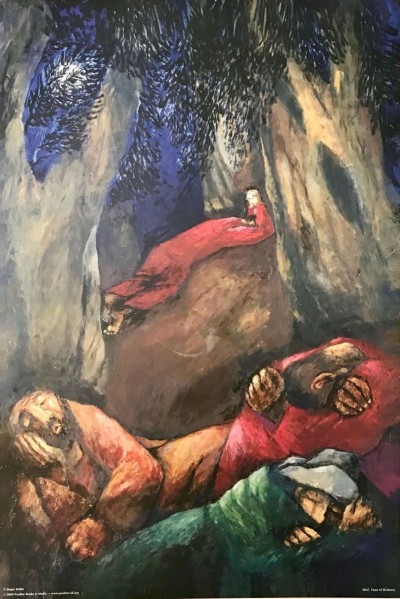

The locations of the Passion take us from the entrance of Jerusalem to Jesus’ tomb, going through the house of Simon the leper, the Upper Room, the garden of Gethsemane, the residence of the High Priest, Pilate’s palace and Golgotha. All these places are important, but Gethsemane continues being the place that moves me the most—the place that, in my opinion, gives more meaning to the experience of the Passion.

Following Mark’s account, after the Passover meal, Jesus and his disciples head to Gethsemane. On the way there, Jesus tells his disciples that they are going to abandon him, announces his Resurrection once again, and predicts Peter’s denial. Upon arriving to the garden of Gethsemane, Jesus displays his full humanity. It is in the garden that we witness Jesus’ struggle. Despite being the Son of God, he suffers like a human. We dare to think that Jesus is not suffering so much in anticipation of the physical pain that he is going to endure on the next day; it is a deeper pain, the emotional pain of giving up a full life, of abandoning those he loved. We cannot strip away Jesus’ humanity, we cannot remove Gethsemane from the way to the Cross. The absolute surrender of Jesus to God’s plan makes sense only if we see how Jesus overcomes, once again, the temptation not to be the Beloved Son of God.

To comprehend this last temptation of Christ, we are reminded that after the celebration of Ash Wednesday, we always begin the journey of Lent on the First Sunday with the text of the Temptations. We read Mark’s this year, where the Temptations only take two verses (Mk 1:12-13.) Luke’s is the Gospel that most clearly indicates that, “When the devil had finished every temptation, he departed from him for a time,” (Lk 4:13) a subtle threat that the devil will come back at an auspicious time. And that moment is Gethsemane.

In Gethsemane, before being taken prisoner, Jesus states that he is dying of sorrow. In the garden of Gethsemane Jesus asks his disciples to pray so that they do not fall into temptation. In the garden the scene of the Transfiguration takes place again (as we see also in Matthew’s account.)

Jesus takes apart the same disciples that he took with him in the Transfiguration—Peter, James and John. Jesus then prays out loud to the Father, whom he addresses as “Abba,” begging him to take away that “cup” from him. He then immediately submits to the Father’s will. Just like in the Transfiguration, the disciples have fallen asleep. Jesus rebukes Peter—whom he calls Simon, he has lost his identity—and commands him not to fall into temptation.

What is the temptation that Jesus experienced? If we realize the parallel with the Transfiguration—which we always read on the Second Sunday in Lent, following the Temptations—if we see that Gethsemane is a parallel with the scene on top of Mount Tabor, we know that the temptation is that Jesus, in possession of his absolute freedom, would choose not to act like the Son of God he is, and would decide not to submit to the suffering of the Cross.

In the Transfiguration, the voice of God tells Jesus’s disciples, “This is my Son, the Beloved.” It is a confirmation of Jesus’ identity that is connected to his baptism, when the same voice proclaims the same message in a baptism that, as Jesus is free from sin, could only be of identity. Thus, this is Gethsemane: a new, last temptation of identity (as all the Temptations really were about!) The Son of Man overcomes in an instant the temptation of not being who he is by not submitting to the Cross.

Holy Thursday accounts and recreates this experience in the Adoration that follows the celebration of the Eucharist. From the end of Mass until at least midnight, we prostrate ourselves before the real presence of Jesus, who has been tossed about for an instant between his love for life and his people and his love for his Father. In Gethsemane, Jesus realizes that both are the same love. It is the Jesus that for an instant begs the Father to strip him from his identity. It is in overcoming this last temptation that fills with meaning and profound love the decision to submit to the Cross.

It is Gethsemane that brings us closer to the human Jesus, human like us, tempted but firm, who suffers, but who loves like we are called to love. It is in Gethsemane that we are shown what we are capable of becoming—of being!—when we feel like children profoundly beloved by the Father.

It is with Gethsemane at heart that we approach and understand the Cross, the absolute submission to the love of God and love of neighbor. With Gethsemane at heart we understand the beauty of the Resurrection that awaits us on the other side of Passover.

May you have a blessed Holy Week.

Nuance is not in fashion. In fact, many people rather find nuanced thinking annoying. The effort to evaluate and examine, with patience, the gradation of tones that exists in reality can be a bother, a waste of time, and even a danger for those who want to understand (and explain) the world in simple terms, in black and white. Simplistic people, of course, were not born yesterday: they have always existed. However, in our day, the accelerated pace of our digitized life encourages and facilitates, perhaps more than ever, simplistic thinking, threatening to turn nuance into a kind of relic of the past. In a world where any opinion on any subject should be able to be summarized in the 140 characters of a tweet, nuance has little chance of succeeding. It should not be surprising that it is not in fashion.

Let's face it: to simplify reality can be tempting. The simplistic narrative is easy to understand. Its characters are flat, their motivations, rough; their responses, predictable; their arguments, shallow. Consequently, in a simplified world it is very easy to choose sides and to distinguish between friends and adversaries, between truth and error, between good and evil.

To point out the nuances of life, on the other hand, demands time—and who has time, in our world of hustle and bustle? It requires that we listen to those who do not think like us, to understand the origins and the intricacies of their arguments. (“How painful,” the simplistic person will say.) It calls for our examination of the history of the processes about which we want to form an opinion. (“Really?” he will add.) Above all, when we begin to think in nuanced ways, we can encounter unpleasant surprises. We may discover, for example, that “our people” have not always been perfect and that “the others” were not always wrong! And so, because of nuance, the black and white narrative can become damaged, and that scares us. To think in nuanced ways reveals a reality full of ambiguities and ambivalences.

The truth, of course, is that a simplified world, however pleasant, will always be a mere caricature of the real world. The vision of those who never point at nuance can offer a semblance of comfort, but it is a myopic vision; and in the end, ignoring the nuance of things will always be an attempt, inevitably treacherous, to reduce complex phenomena for our convenience. Like it or not, life is complex, and the nuance, therefore, essential.

Without it, we have many possibilities of falling into ignorance: nuance is a potent antidote against fanaticism. In addition, a society that stops thinking about things with depth and subtlety becomes sick with shallowness, and will soon discover that it lacks the necessary tools to face its challenges, because no serious problem will ever be solved by denying its complexity.

To think in nuances, therefore, is not an option: it is an obligation. And it is an obligation, especially, for those in leadership. To have a political class which thinks in gross generalities is among the worst thing that can happen to a country, and the sad spectacle of presidents who play at governing from their twitter account is a mockery to its citizens. Today, unfortunately, the list of countries guided by political classes that despise the art of being nuanced seems to increase.

In this context, it seems to us that it is critical to applaud the nuance. We need a passionate commendation of the art of nuancing: yes, a commendation of this annoying, old fashioned, boring, uncomfortable—and absolutely essential— art, without which we would return to the Stone Age or the Inquisition. The desire to point to nuance characterized neither our prehistoric ancestors nor the fanatical and myopic defenders of orthodoxy.

In the middle of a violent racist episode, a chapel became a temporary refuge for a Haitian family

Last month, an immigrant from Haiti robbed and killed a farmer from Sabana Yegua, Azua, Dominican Republic. It was an atrocious act. The perpetrator was immediately captured and is now in the hands of justice. The crime was then followed by a disproportionate and irrational reaction against all Haitians who live in the town, which is the headquarters of La Sagrada Familia Parish. The same night of the crime, a group of people (some with criminal records) took to the streets of the town, beating and, with machetes, attacking several Haitians. They set three homes on fire, robbed and took away property from Haitians, excusing it all as retaliation for the death of the farmer.

From that moment, Haitians in town feared for their lives; many returned to Haiti, and others hid themselves in the fields, outside the village. We, as representatives of the Church, called local authorities and mobilized several organizations to stop the brutality that was occurring, asking for compliance with the law, civility and peace.

Intolerance and xenophobia against Haitians have been present for a long time in the Dominican Republic. They have deep historical, economic and social roots, and produce cyclical altercations and episodes of intolerance. When this happens, there are always voices who make the ridiculous accusation that the neighboring country (Haiti) is carrying out a peaceful invasion of the Spanish-speaking side of the island. Historical episodes from the past are mixed with present day immigration circumstances; yet, they are completely different. In fact, today Haitians are a key part of the economy of the Dominican Republic, as a workforce in agriculture, and there is no doubt that the Dominican Republic’s exports to Haiti are very important for the nation’s commerce.

Joselito, a 45-year-old man from Haiti, arrived in the DR as a twelve-year-old orphan looking for a better life. He admitted to me that he was terrified, and that he needed protection. He and his wife, Melady, have ten children, and as is the case with many families, it is very difficult to give their children all that they need. Yet, Joselito and Melady have never committed a crime and are legal residents in this country. Their children were born here and are now completing high school. He was afraid that they could be the target of the anger of those attacking Haitians just because of their nationality.

We decided to move Joselito and his family to the new chapel in Tábara Abajo, a town located a few miles away from Sabana Yegua. Therefore, this little chapel, which was inaugurated in December, had the honor of sheltering a foreigner in need of lodging. For one week, the family stayed there, without beds or furniture. At first some neighbors were suspicious, but common sense prevailed. In fact, a neighbor told us that many Dominicans have family in the USA, Spain, Italy and Switzerland: these are people who have immigrated in search of work, and none of them would like to be judged because of a crime committed by another person. Those who sparked the outrage tried to continue the talk of expelling all the Haitians from town. However, they were not supported, and finally things returned to normal. Nevertheless, it’s important not to lower our guard, for it is obvious that what happened was very, very grave.

It is essential that the law may act against those who commit a crime, regardless of their nationality, and we must promote coexistence, respect and dignity for all people. In any case, the church which is made of living stones (that is, all of us) and the church/temple (that is, the building) should always be a sheltering and welcoming place, a true home for everyone. On this occasion, our humble chapel at Tábara was just that, in a concrete and tangible way.

The word for Lent in Spanish is Cuaresma, which comes from the Latin Quadragesima; that is, forty in ordinal numbers. That is because Lent (or Cuaresma) has as a direct root the forty days that Jesus spent in the desert fasting. The Church’s celebration of Lent is a tradition that goes back centuries. Nevertheless, with time and because of the idiosyncratic nature of the Church around the world, there is a biblical element that is an essential part of Lent that sometimes is left behind: Baptism. To see this clearly, we must go to the Gospel readings during this Lenten season.

There are several key Gospel readings for Lent, the first of which is the focus on Ash Wednesday. Every year, the reading is from Matthew, no matter the cycle. From there we have the three distinct practices of Lent: fasting, prayer, and alms-giving. And we are also reminded how we are to fast, pray and give alms. Jesus says: Take care not to perform any of these deeds that people may see them! (c.f. Matt. 6:1). The Gospel for the first Sunday of Lent does change according to the cycle, but they each focus on the same event in the life of Jesus: the temptations of Jesus during his forty days in the desert. Likewise, the reading for the Second Sunday also changes but focuses on the Transfiguration. With this common foundation, we then have different Gospel readings taken from John and Luke for the Third, Fourth, and Fifth Sundays.

Having the context of the readings, let us return to the First Sunday of Lent. Here, we will find ourselves with a very well-known passage in the Bible, that of the temptations of Jesus. In all of the Gospel traditions, we find that the reason why Jesus goes to the desert has to do with the Spirit. In Matthew, Jesus “was led up by the Spirit into the wilderness to be tempted by the devil.” (Matthew 4:1). Luke writes that “Jesus, full of the Holy Spirit, returned from the Jordan and was led by the Spirit in the wilderness, where for forty days he was tempted by the devil,” (Luke 4:1-2a). And finally, what we will hear this year in Mark: “And the Spirit immediately drove him out into the wilderness. He was in the wilderness forty days, tempted by Satan…” (Mark 1:12-13a). No matter the Gospel, the Spirit leads or drives Jesus out into the wilderness to be tempted.

Of course, this is not the first appearance of the Spirit; it has been introduced just before at the narrative of Jesus’ baptism. If we read Mark carefully, we find the adverb immediately, suggesting that the temptations are an urgent step for Jesus right after the baptism. In other words, the Spirit that Jesus received during his baptism, the one who came down as a dove, will produce this quick movement into the wilderness.

This shows a direct relationship to Baptism and facing temptation. At the baptism of Jesus, there is a voice from heaven that says Jesus is the beloved Son of God. And when we read the temptations, described in detail by Matthew and Luke, we realize that two of them start with the interrogative sentence “if you are the Son of God…” The voice of the tempter is in diametrical opposition to that of God. The temptations of Jesus in the desert, while provoking him to use his divine power to personal benefit and for the sake of display, are at their core the same temptation: to demonstrate that he is indeed the beloved Son of God. The tempter is putting the voice heard at Jesus’ baptism in doubt. The moment Jesus acts on the temptations, he already doubts the voice from heaven. It is then reasonable to believe that the Spirit that Jesus received at his baptism has driven Jesus into the desert to fasten his identity as the beloved Son of God; so that the love of the Father would never be put into doubt throughout his mission on the way to the cross.

I would suggest that the reaffirmation of our identity as beloved sons and daughters of God should be precisely one of the primary purposes of these forty days we call Lent. Our Baptismal Identity is crucial to understanding why Lent even exists. It is true that during Lent we practice penance as a way to be prepared for the Easter celebration. But while penance is necessary, it is not the first or only step in our Lenten preparation. Again, an essential part of Lent is to remind ourselves that we are beloved sons and daughters of God, and our acts of penance should direct us towards an experience of this.

As mentioned before, we will hear that voice again from Jesus' baptism during the Second Sunday of Lent. At the moment of the Transfiguration, a voice from heaven will remind the disciples: this is my beloved son. So, this Lent let us not forget our Baptismal identity. Before we rush to do penance, let us first evoke our identity as children loved by God. In doing so, our penance will be more profound, dynamic and fruitful.

Reflection on the Feast of Candlemas

On February 2, the Feast of Candlemas, my parents, who have been married 59 years, usually attend the annual celebration Parents of Alumni of the Marists Brothers’ school in Badalona (Spain). On that day, we commemorate the presentation of Jesus in the temple. It is a special day because in many places spouses also renew their marriage vows, and World Day of Consecrated Life is celebrated. This beautiful feast prompted me to write this reflection.

The presentation of Jesus at the temple by his parents was an act of obedience to the Law of Moses, according to which a child had to be presented at the temple 40 days after his birth. February 2 is, of course, 40 days after Christmas. According to the Law, the first born son of each home belonged to our Lord, and parents had to present the child and pay a ransom for him at the temple.

The presentation of spouses at the temple, to renew their marriage vows with each other and the Lord, is very appropriate for this day. So, too, is the celebration and renewal of vows for those who have consecrated their lives to God. Like the first born of each Jewish family, they also belong to the Lord. This belonging of believers is characterized by fidelity.

Sometimes it seems that fidelity, the “forever” option, is not in style nowadays, except for those who want tattoos. In a time like ours, where options are abundant, with a great range of opportunities and many open doors during the trajectory of one’s life, it has become difficult to choose definitively one road over everything else. Isaac Riera, MSC, wrote about “the weakened will” and claimed that “modern man is full of stimulation, sensations and desires, but lacking in willpower”. Perhaps this explains the lack of perseverance in some marriages and even the decline of vocations to a consecrated life.

Nowadays, fidelity has for some a negative undertone, as if it were a value of bygone days, related to resignation and prohibitions. However, it is actually a free, beautiful and creative exercise. Faithfulness is a choice, a promise, a fundamental option, whether it be as a couple, to children, to a principle or to a profession. It implies coherence with oneself and perseverance to face many obstacles.

Bishop José Grullón, of San Juan de la Maguana in the Dominican Republic, speaking recently about perseverance to a group of couples who were happy with their marriages, posed the following question to them: “What is better, to win someone’s love or to preserve it?” To the response of many that “to preserve” is better, he explained that “to preserve love” is to leave it frozen, paralyzed. On the contrary, “to win someone’s love” is something that must be done every day. The Spanish songwriter Victor Manuel says it in one of his songs: “Day to day I grow within, because I love you. I keep fanning the fire”.

Today, Candlemas, we remember our fundamental option and our fidelity, a creative and renewed fidelity. It is a faithfulness that we pursue day to day, every day, fanning the fire to keep alive the flame. Because our choices and fundamental options, not just our tattoos, are forever.

In the United States we celebrate the Feast of the Epiphany this Sunday, in other parts they do it on the actual day, January 6. This is a beautiful celebration, not just because it’s a time for presents in many cultures, but also because of the profound theological message behind it. The Magi, coming from afar, gentile nations, search out and encounter Jesus, the Messiah. The relationship between the encounter of peoples and their encounter with God and salvation, is at the center of who we are as the Catholic Church.

I began to see the importance of the Church being a place of encounter during my years of formation with the Community of Saint Paul in the Dominican Republic. I became involved in our work with the Haitian immigrant community living within the territory of La Sagrada Familia Parish. Many of those reading this know that the relationship between the two countries is far from cordial. Over time, we developed a Haitian Ministry program, becoming one of the few parishes in the region to have one. Then we began to have more opportunities and events aiming at bringing the two different groups together in prayer and community. And I am very proud that the Community of Saint Paul continues to develop more opportunities for this to happen.

Now I am serving in my first assignment as a priest in St. John Paul II Parish on the Southside of Milwaukee. We have a good-sized English-speaking community, with a large and growing Spanish-speaking community. And the diversity goes beyond language, as we have several different countries of origin within the Hispanic population, and our parish is the merger of what was once three separate neighbor parishes in a part of the city that was very neighborhood-based. Inspired in part by my experiences in the Dominican Republic, I am involved with a group in the parish that focuses on building unity in St. John Paul II from within this diversity.

The parish setting should always be a place of encounter and unity, with one another and with God. This is so central to who we are that every Sunday we profess it in Mass. Unity is the first of the four marks of the Church within the Creed: one, holy, catholic and apostolic. And there is of course a direct relationship with “one” and “catholic,” meaning “universal.” It is in this sense that the Second Vatican Council taught that the Church exists in Christ as the “light of humanity,” as a “sign and instrument” of communion with God and unity among all humanity.[1]

The inherent connection between the unity of peoples and the unity of humanity with God is not new. Rather, it has deep roots in Judeo-Christian theology. For example, one of the main oral traditions in ancient Judaism regarding the culmination of Salvation History uses the image of all nations (think “peoples”) gathering on God’s mountain and recognizing Him as God. We can see this captured, for example, throughout Isaiah[2]. In this way, the unity of peoples takes on an eschatological importance, pointing to the end of time.

As those rooted in this tradition, it is not surprising that the early Christian communities would see in Jesus the beginning of the unity of all peoples with the fullness of God’s salvation. We even have an example of this in our reading last Sunday from the Gospel of Luke for the Feast of the Holy Family. Simeon sees in the child Jesus that his “eyes have seen [God’s] salvation which [he] prepared in sight of all the peoples, a light for revelation to the Gentiles.”[3] Part of the fulfillment of God’s promise is the aforementioned connection of the unity of all peoples, and the fulfillment of salvation.

With this in mind, we can turn to today’s Gospel reading on the Feast of the Epiphany. Matthew, of all the evangelists, has a particularly “strong knowledge of and attachment to Jewish Scripture, tradition and belief.”[4] Most scholars believe that Matthew was writing for a Jewish-Christian community that was struggling with the diversity it was experiencing as more Gentile-Christians were joining them. Accepting this thesis, it makes sense that especially Matthew would strive to show how Jesus is the fulfillment of what was promised by God in “the scriptures,” of the Torah and the prophets.[5] This is the “epiphany” of this Feast day. Coming from “the East,” the Magi represent Gentile nations who come to Jesus to pay homage to “the king of the Jews.”

This is reflected throughout Matthew’s Gospel, from the beginning, with the visit from the Magi, to its end where the resurrected Jesus commands to his disciples to go out and to “baptize all nations.”[6] For Matthew, the connection between the unity of peoples and the fulfilment is not just a theoretical discourse, but points to the importance of the practical reality his community was facing and with which they struggled. The Magi “prefigure those Gentiles who are part of Matthew’s community.”[7] Writing for catechetical purposes, Matthew reminds his community, and us, that striving for unity is of utmost importance in the long tradition of its eschatological significance: the unity of peoples is linked to the fullness of the Kingdom of Heaven.[8]

There may have been times when we have taken for granted the importance of unity within diversity, as it became a common catch-phrase throughout our schools, universities, workplaces and social outreach programs. It is perhaps in part for that reason that it seems many societies are sadly moving away from it. But this should never happen within the Church. We can never lose sight of this ancient and profound spiritual principle of the unity of peoples being linked to the fullness of God’s Kingdom. While it is something “nice,” building unity is so much more to who we are as a people of faith, especially as disciples of Jesus.

As we celebrate the Magi, let us be renewed in our evangelical fervor to reach out to and unite all peoples. Times of sharing, like cooking classes, pot-luck dinners and bilingual-liturgies may not be easy, but they are an essential step in who we are, called to be one, holy, universal and apostolic Church.

[1] Lumen Gentium 1

[2] See for example Is 28:6, 43:9, 56:6

[3] Lk 2:30-32.

[4] Gale, Aaron M. 2011. “Introduction to the Gospel According to Matthew” in Jewish Annotated New Testament. Oxford University Press. p. 1.

[5] Ibid

[6] Mt 28:19.

[7] Harrington, Daniel J. 1991. The Gospel of Matthew. In Sacra Pagina commentaries. Liturgical Press. p.49.

[8] John Nolland argues that the Gospel may have been written as a sort of Catechetical manual for discipleship, which is directed toward the eschaton. He writes that the author’s self-understanding many be reflected in Mt 13:53, in being “disciple [to be] a scribe for the kingdom of heaven.” Nolland, John. 2005. The Gospel of Matthew. In The New International Greek Testament Commentary. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. p. 20.

Christmas is a very popular feast, and there is no doubt that we are invited to celebrate it from its clearly Christian perspective, assimilating the more theological dimensions that it offers us.

One of these dimensions would be to see Christmas as a sign of communication: communication from a God who made Himself one in the midst of us, to transmit His message of salvation and love. In a society such as ours, in which communication advances faster and faster each day, and in which it seems that we are always connected, it’s good to reflect on how the feast of Christmas can help us.

God communicates Himself with tenderness: there is nothing more tender and fragile than a child. God doesn’t express Himself with violence, nor with big banners or billboards. He expresses himself with the sweetness of a newborn baby whose face is etched with traces of kindness, compassion and the love of His Father.

God communicates Himself with simplicity: “She gave birth to her first-born son and wrapped him in swaddling clothes and laid him in a manger”. Jesus’ birthplace is humble. In a society frequently drunk with consumerism and abundance, the feast of Christmas is a call to live what is important, to discover that the best gift we can receive is the company of our family and friends.

God communicates Himself with hope: “Do not be afraid. I come to proclaim good news to you, tidings of great joy to be shared by the whole people” say the angels to the shepherds. As worried as we may be with the problems of life, and as dark as we may view at times the social or ecclesial landscape, it is good that we allow ourselves to become filled with the happiness and the hope of today’s celebration. It is urgent that we Christians may proclaim, for ourselves, and for all willing to hear it, a message of joy, underscoring the blessings that come from God through the feast of the birth of His Son.

Let us allow the feast of Christmas to speak to us and help us improve our communication. That tenderness, simplicity and hope may help us communicate the joy of Christmas.

One more year, we embark again in the path of Advent, a path of hope, but above all of joy for the feast that is about to come. Unlike Lent, Advent is not a time of penance, but of preparation for the first great event celebrated by the Church in its annual calendar: the feast of God’s closeness, who lowers himself to embrace the human condition in history, offer his solidarity, and elevate us to his own dignity.

As we would do before any other great event in our lives, we cannot sit down and just wait, doing nothing, to see what happens next. Advent is a time of active preparation, which demands our commitment and requires us to clear any obstacle so that the feast can be celebrated in the best possible conditions. We will hear these days the prophets speak of the need to «fill up the valleys and lower the hills», and thus prepare the ways to the Lord.

«The one who waits, despairs» is the logic of the world, of those who limit themselves to receiving, with resignation, what life can offer them, but without getting involved in the events that happen around them. Christian hope, on the other hand, becomes the impulse to go out to transform the world, so that the advent of God will find us ready and awake, yearning for a better world.

The Community of Saint Paul, small as it is, takes part in the work carried out by the Church throughout the world, to transform the social and even the economic environment as leaven in the flour, making a difference in the fields of human development, education, health, human rights and the dignity of others, especially of those who suffer poverty and exclusion. It is the task to help clear, one by one, the obstacles that separate us from God’s plan for humanity.

With the renewed joy and strength of those who know that a better future is about to come, we intend to continue working to break down walls, build bridges and heal wounds in a world still full of divisions, and invite all our readers and friends to join us in this Advent project, because we are not willing to accept, just like that, the “valleys and hills” of history that surround us.

You do not have to be very insightful to see that we live in a world that tends toward polarization. There are plenty of examples of societies that in recent years have seen how their populations were configured in terms of some tension (economic, political, cultural, or a mixture of all of these) to end up polarized into two groups, similar in size, and ideologically apart. Let us think of some examples, without going into a detailed analysis of any of them: for instance, the United States, a country that in the last presidential elections experienced a bitter division between the supporters of one candidate and another. Finally, the Republican candidate received the 46.1% of the votes cast, and the Democratic candidate 48.2% (although, as is well known, Trump became the president because of the US electoral system). Or think of the referendum on the permanence of the United Kingdom in the European Union, the passions it raised, and its result: 51% of voters chose the winning option and 48% lost. Or the referendum on the peace process in Colombia, even tighter: 50.21% of Colombians voted “no” and 49.78% “yes.” These days, to give one last example, the situation in Catalonia has occupied the first pages of the international media, because of the independence movement that exists there. In the last parliamentary elections (2015) the parties that support independence from Spain obtained 47.7% of the votes, and those not in favor of independence 52.3%.

All these cases, while different, exemplify something similar: how, in matters of great importance, the societies that confront them do not clearly favor one option over the other. Neither the defenders and detractors of Trump, nor those of the Brexit, nor those of the peace agreements in Colombia, nor those of Catalan independence, can boast of having an evident and unappealable social majority. In each case, the winning alternative wins with just a little more support than its counterpart. In addition, the cases cited have in common that the issues at stake generate an extraordinary passion, so that those who support and those who reject one option or another do not want to hear about a compromise solution with the adversary, because to them the opposite position is simple unacceptable. We live in a polarized world.

It seems to us that, in this context, a voice becomes essential: the voice of what we could call the “third way” (borrowing the language that has been used in economics to identify those who propose an intermediate system between capitalism and communism).

Often, in the midst of festering conflicts that shake a society, people or groups emerge that shun the overly simplistic discourse of the two opposing parties and try to elaborate a different, original argument that cannot be pigeonholed on either side. It is the intermediate way, the third way. These tend to be minority and unpopular, precisely because those who defend them want to take into account the complexity of situations and all its nuances, for which others have no time or, indeed, interest. Conflicts (social, political, religious) tend to feed on rather schematic approaches, unfriendly to the thoughtful reflection proposed by the third ways. It would be useful, here, to remember the warnings of the anthropologist René Girard on how crowds normally act: impatiently, without attention to detail, and making easy caricatures of their adversaries. These are attitudes that hinder dialogue and feed the birth of populist tendencies, which in turn can open the door to violence.

A third way will rarely express itself through large demonstrations in the street: marginal, it is often underestimated by the main currents of opinion, which deep down perceive it as a threat to their approaches. Many times, at last, the voice of the third way falls into oblivion. And yet, it is more than likely that the best proposal for the future resided in it.

Those who advocate for a third way can be as radical, vigorous and passionate as those who defend more extreme positions: “third way” does not mean lukewarm at all, but having the will to think in depth, to consider all aspects of the conflict and to reject the appeal of an argument which is attractive in its simplicity, but false because of it.

Many historical representatives of the third way have paid a high price for their commitment to reality and for refusing to fall into populist and sometimes violent simplifications, often ending up rejected by all: and it should not surprise us that many times it has been fanatical elements of their theoretical own “side” those who have eliminated the advocates of a third way. The twentieth century gave us clear examples of this phenomenon. Consider the pacifist and internationalist socialism of Jean Jaurès, who would be assassinated in Paris by a French patriot the same day that the First World War broke out. Even better known are the cases of Gandhi, murdered by a Hindu extremist who did not accept the openness of the father of Indian independence towards the Muslims, or Yitzhak Rabin, killed by an Israeli who opposed the attempts of his prime minister to discuss peace terms with the Palestinians.

From a Christian perspective, to what extent would it not be also legitimate to consider Jesus of Nazareth as representative of a third way, amid the political and social conflict in which he lived his life? He did not approve of the stance of the powerful class in Israel, the Sadducees who ruled in Jerusalem and collaborated with Rome, about whom he had tough things to say, but he did not endorse either the option of the fanatical nationalists, who advocated violent rebellion against the Empire. And, undoubtedly, he upset everyone with his message, free of ideological alliances: Jesus was able to say of a Roman centurion that “I have never found so much faith among the Israelites” (Lk 7:9) and capable, at the same time, of challenging Roman authority when affirming, before the governor who was judging him, that “you would have no power over me unless it were given to you from above” (Jn 19:11). His message, demanding with everyone but also open to all types of people, was misunderstood by the majority. Ultimately, adversaries of all sorts were interested in taking him out of the way.

Endorsing with resolve a third way to attempt to correct the polarization of the society in which one lives can be dangerous. And yet, in our world today, so inclined to defend seemingly irreconcilable extremes, the voice of those who advocate for dialogue, inherent in the third way, seems to us indispensable. Perhaps more than ever.

As it was reported by the media throughout the world, from the 6th to the 10th of this month of September, the Pope made his expected apostolic visit to Colombia. It was five very intense days. Intense and exhausting, in the first place, no doubt, for Francis himself, who was in Bogotá, Villavicencio, Medellín and Cartagena presiding at huge gatherings (in each of these cities, those attending the events surpassed all the organizers’ projections), celebrating the Eucharist and having an endless number of meetings: with representatives of the Colombian government, with the youth, with victims of the armed conflict, with religious, with bishops, with people who crowded the streets through which he passed and with those who spontaneously concentrated around of the Apostolic Nunciature of Bogotá, where he stayed. It was also an intense visit for all those who followed it closely: the days were very rich in gestures, in moving moments, in strong messages that deeply touched the country.

Francis had said that he would go to Colombia when the government and the guerrilla would have signed the peace agreement that ends more than 50 years of armed conflict. He has fulfilled his promise, making of his trip an invitation to the reconciliation of all those whom war and violence have confronted for so long.

One reflects now on the pope's visit and realizes that he has left us a universal message: that is, a message that goes beyond the Colombian situation, that transcends it, and that we all can apply to ourselves, whether we are in Colombia or not, if we are concerned about conflicts and violence, if we long for paths to peace and reconciliation. Francis, in his clear and transparent language, has invited us not to be spectators in the construction of peace: “When the victims overcome the understandable temptation of revenge, they become the most credible protagonists of peace-building processes. It is necessary that some are willing to take the first step in this direction” (Homily in Villavicencio, September 8). Again and again, the pope has insisted that we should not resist reconciliation, that we should not be afraid “to ask forgiveness and to offer forgiveness”: “It is time to deactivate all hatred” (Prayer for National Reconciliation, Villavicencio, September 8).

In a world where so many quickly gravitate towards resentment and revenge, and where conflicts, real or imagined, tend to become entrenched, this recommendation (“it is time to deactivate all hatred”) seems essential to us. Essential, in spite of its difficulties. Francis knows how to make his invitation sound as achievable (because it truly is!), the very same invitation that, in somebody else’s mouth, would seem like a fantasy or an empty plea. Deactivate hatred. Forgive. Why not? The gentleness that emanates from the Pope, with his simplicity and lavish smile, enables him to communicate, without offending anyone, a message that in the mouth of another would seem too harsh, and it would most likely be rejected.

A taxi driver from Bogotá expressed this same thought very frankly, and with a certain astonishment, the afternoon of the Sunday when the Pope had finished his visit and had just embarked on his flight to return to Rome. “If someone else told me the things he says, I would not want to hear him. But this old guy has a way of correcting you that makes you pay attention. When I saw on TV that he went into the plane to fly away, I burst into tears.” Francis’ visit to Colombia could not be better summarized.

The study of Professor Ruster, sometimes dense, has many merits. Here I would just like to echo one of his arguments, one that undoubtedly has implications for everyday life: I mean Ruster’s description of capitalism as a religion—and as a religion which, in essence, stands in opposition to biblical doctrine.

Indeed, beyond the designation of capitalism as a religion, what has most captivated me is his dissection of the mentality that underlies capitalism.[2] This, he points out, is born out of concern for an uncertain future. The yearning for accumulating wealth for tomorrow is based on the conviction that available goods are limited (that is what Ruster calls the doctrine of scarcity) and that therefore the natural duty of any sensible person is to secure today, as best one can, the always uncertain sustenance for the future. Nothing can perform this function as well as money, and no mechanism better ensures the existence of future income as does interest. In the words of John Maynard Keynes, whom Ruster quotes, “the importance of money comes primarily from the fact that it represents a link between the present and the future.”[3] And Ruster continues: “The preference for liquidity has psychological reasons, and is born of concern for the future itself.”[4] In other words, money is at the service of foresight, and capitalism “is religious in the sense that it attempts to ensure the future, through money.”[5] The typical capitalist mentality, in short, would be born of a strong awareness of scarcity; its result would be the exercise of foresight through the accumulation of goods that today we do not need, but that we may need later.

This mentality clashes head-on with biblical doctrine. The instruction of Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount could not be clearer: “Do not pile up treasures on earth” (Mt 6:19). “Do not worry about your life thinking about what you are going to eat or drink” (Mt 6:25). “These are the things for which the gentiles are concerned” (Mt 6:32). And what is fundamental: believers should ask only for their “daily bread” (Mt 6:11). Already in the Old Testament the people of Israel learned the lesson of the manna: what is collected for more than a day rots (Ex 16).

It is not that biblical faith praises irresponsibility; the Bible is not a call to live without care, but it is an invitation to live trusting in God, not money. And there is something deeper at stake, at which we wanted to arrive with this brief reflection: to understand that, as Keynes himself observed, there is a connection between supposedly responsible, future-oriented behavior (born of the capitalist faith in scarcity) and injustice. A direct connection: behavior that we have come to think of as responsible and prudent is often the cause of injustice. In this sense, the renunciation of foresight, far from being irresponsible, is born, as Ruster affirms, “from faith in the fullness of the divine blessing, and is at the service of the kingdom of God and its justice.”[6] The well-known Biblical prohibition against the collection of interest (Ex 22:24; Lev 25:35-37; Deut 23:20-21) should be understood as a warning in favor of social justice: no future enrichment should be sought at the price of the indigence of the poor in the present. For in short, “there is enough for everyone if there are not some who secure their future at the expense of others.”[7]

It is difficult to read Ruster’s work, and to then observe the societies in which we live and not to see the formidable relevance of his argument, because inequality between nations and within nations is today one of the most pressing problems of humanity. This is, for instance, Jared Diamond’s conclusion at the end of his recent little book Comparing Human Societies,[8] and in fact it can be seen by anyone who opens a newspaper or goes out to the street. The appalling data are, unfortunately, well known: 62 people have the same wealth as the poorest half of humanity (3.7 billion people). The richest 1% of the planet already has as much as the other 99%. You look at the reality of any Latin American city (or, for that matter, European or North American or anywhere in the world) and the abysmal inequalities are obvious. Differences in housing, salaries, education or health services among its more affluent inhabitants and the poorest—who are the majority—are scandalous.

How can we not see that such inequality makes peaceful coexistence impossible? How can we not realize, whatever religious faith moves us—or if we do not have any—that there is in this inequality a profound immorality? How did we get here?

How? By following the capitalist creed, the pernicious doctrine of scarcity. And by contravening the biblical doctrine which invites us to ask only for our daily bread. The issues raised here are complex, and we would not want to simplify them. However, it is quite evident that greater historical fidelity to the biblical doctrine of the abundance of God and the invitation to seek only our daily bread would have prevented us from reaching the tragic and dangerous situation of inequality in which we find ourselves today. It would seem that Keynes was right when he demanded an active state policy that would limit the personal greed of the individual. Such a policy would be in full harmony with the Gospel of Jesus.

[1] T. Ruster, El dios falsificado (Ediciones Sígueme, Salamanca, 2011).

[2] To offer this “dissection”, the German theologian quotes authors as Walter Benjamin and, even more, John Maynard Keynes.

[3] T. Ruster, op. cit., 168.

[4] Ibid., 169.

[5] Ibid., 174

[6] Ibid., 176

[7] Ibid., 177

[8] J. Diamond, Sociedades Comparadas (P. Random House, Barcelona, 2016).

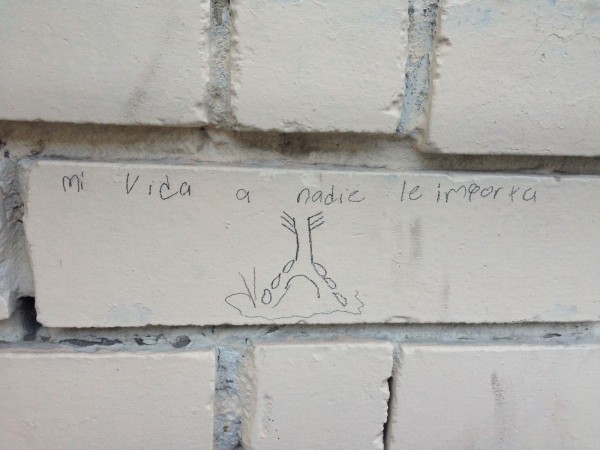

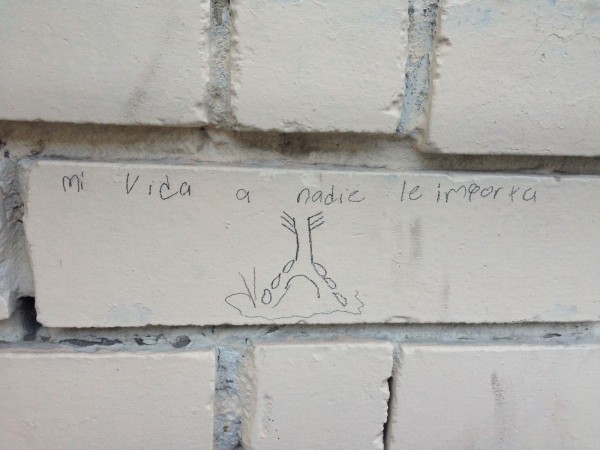

A few days ago, I noticed, by chance, a tiny bit of graffiti made with pencil on a brick of the outside wall of a school in the El Pesebre neighborhood of Bogotá. The phrase was written in small print, clearly childish, but it could be read without difficulty: “No one cares about my life.” And below the letters, occupying the whole height of the brick, more or less below the word “nobody,” the simple drawing of eyes shedding tears above a sad, inverted U-shaped mouth. I was so struck by this, I took out my phone and took a picture.

I will never know who was the author of this street art, that with the passage of time, or after the first rains that fall on the city, will be erased. But it is easy to imagine the scene: the boy or the girl —let’s imagine that she is a girl, and let’s say that she is eight or nine years old— leaves her classroom with sorrowful eyes, at the end of the school day. The companions go, each to his house. She is alone in the street; the pain overwhelms her, who knows what sadness and turmoil cloud her joy? And then, before she continues with a slow and self-absorbed pace towards her home —where perhaps the reasons of her anguish live— she stops. She has had an idea. She looks up and down the street: no one. She pulls out a pencil from her school bag and writes her concise message on the wall: “No one cares about my life.” Then she completes the sentence with the scribble of a weeping face. Perhaps when she is done she contemplates her work —her cry— for a few seconds. Then she saves the pencil and leaves, maybe a little relieved.

I am impressed by the gesture and the message.

First of all, the gesture: to write rage on a wall is undoubtedly due to the fact that the graffiti writer felt, at least at the time, that the wall was her only interlocutor, that is, she had no one of flesh and bone with whom to share her sorrows. At the same time, recording her frustration on a neighborhood wall was a way to make her voice heard: “Someone will read me,” the girl must have thought. “That my confession has no signature and nobody knows that it was me who wrote it is the least important: someone will read and know that here, there is someone whose life does not matter.”

And I am struck also by the message, which sums up in six words a drama that is, of course, the drama of many people: the weight of their own irrelevance, the feeling that they matter to no one. Neither to parents (are they absent?) nor to other relatives, or to friends, or teachers…

Is it true that nobody cares about this girl’s life? I do not know. However, I know that she feels this way. And I know that this small bit of graffiti, which is a lament, a cry and a complaint all at the same time, condenses perfectly the expression of a fundamental human yearning, which we would do well not to forget or lose sight of: the legitimate yearning for relevance, to desire to matter to someone, of not being treated as if completely insignificant.

The anonymous protest of this girl helps us to understand that few things are so critical in our relationship with others as to communicate how much we care about them. It is not a question of offering, artificially, forced declarations of love. But between this, and never saying that we love each other, it is better to sin by excess. Let us humbly acknowledge our need to be loved. Let us not be stingy in our manifestations of affection. They cost nothing, and yet they can transform lives.

As is well known, the word "Pentecost" comes from the Greek and means the fiftieth day. The number 50 is, for the Jews, a symbol of fullness: a week of weeks (seven by seven, plus one). This feast, which originally had an agricultural character, is celebrated fifty days after the Jewish Passover. It is thought that fifty days after the exodus from Egypt, the people of Israel sealed the covenant with Yahweh on Mount Sinai under the guidance of Moses.

Today, seven weeks after Jesus’ resurrection, Christians celebrate the outpouring of the Spirit to the apostolic community, not as an independent feast, but as the culmination of Easter: "Receive the Holy Spirit!"

In the midst of the bustle of people of different tongues who came to Jerusalem to celebrate the Jewish Pentecost, the Holy Spirit gave the apostles the strength to communicate Jesus’ message of love to all. After the departure of the Lord, confusion and dispersion could have triumphed, but the Holy Spirit inspired the community of disciples to work for the common good and to share the message of unity with all the nations. In this way the Risen One reaches the ends of the earth.

In a society as polarized and fragmented as ours is, we need to live celebrating Pentecost. We ask for the presence of the Holy Spirit, and we can say:

Come Holy Spirit, teach us to dialogue as brothers and sisters.

Come Holy Spirit, help us to understand the language of the adversary.

Come Holy Spirit, teach us to discover that we are all brothers and sisters.

Come Holy Spirit, free us from the threat of turning our countries into a new Babel, incapable of building a future of fraternity.

Come Holy Spirit, and free us from intolerance, from stubbornness, which increasingly distances us from all effective collaboration.

May we repeat among ourselves those words of Paul to the first Christian communities: "Do not stifle the Spirit" (1Thes 5,19). Let us not weaken our faith in the Father of all, and let us not quench our hope for a more fraternal society.

At the beginning of Lent we meditated on the contingency of our existence, about the teachings of the phrase, “You are dust, and to dust you shall return”. We pondered the benefits of being well aware of our finite nature. Today, on the great feast of Easter, we seek the road to the Resurrection.

Easter is the celebration of new life, new creation, rebirth, transformation; it is happiness, interior peace, profound joy. Perhaps in life we don’t seek these goals following a straight linear road, but rather through a cyclical route, transported by the waves of life. We go forward step by step, not without stumbles and setbacks, maybe taking some detours... pursuing a slow spiral, and we do it embracing the cross. That personal cross, those limitations that we are conscious of, those hidden selfish acts, the jealousies and lazy habits that betray our lofty goals; it is simply necessary to bear those crosses. There is no way around it: As the evangelist says, “Take up your cross and follow me.” A key to the cross is accepting, embracing, gathering up everything that is difficult to bear. Accepting, for instance, how silly we can be at times; accepting the deceptions in which we entrap ourselves, like in the web of a spider; accepting the illness that reveals to us how human and fragile we are; accepting the dependence on others for so many things; and accepting and embracing the imperfection of our world, of the humanity that God created free, with all its miseries and vanities, capable of the most beautiful gestures and the worst atrocities.