“Post-truth”, Mark Twain and our fears

Apparently, we live in a world that values truth. If we were asked what virtues we expect to find in our political leaders—and in intellectuals, scholars, artists, journalists, etc.—surely many of us would mention integrity and honesty, without having to think too much about it. We want to believe that our society applauds those who tell the truth and repudiates those who lie.

However, is that so? To what extent do we really care about the truthfulness of the politicians we vote for, the analysts we listen to, and the authors we read?

It is pertinent to ask ourselves these questions because, in fact, the evidence suggests that the current public debate is filled with lies and liars. Political leaders of every stripe place themselves daily in front of microphones and without much hesitation tell us half-truths, distort facts, omit information, and declare things that they do not know. So much so that we have even coined a term, the euphemistic "post-truth," to speak of this phenomenon.

But perhaps this is not the main issue at stake: there have always been characters who thought that deception was the fastest way to power. The question that we would like to explore is a different one: we want to ask ourselves to what extent we live in the post-truth era because we— ordinary citizens— allow it. Why do we allow them to lie to us?

The problem, indeed, may be not so much the leaders who offer a discourse in which reality is distorted, but the population that applauds them despite their lies. Perhaps what happens is that (contrary to what we say to ourselves) we do not seek, above all, leaders whose commitment to the truth is unquestionable. Perhaps what we look for in our leaders are other things, and we are more than willing to renounce truth if this is the price to pay to obtain these “other things.”

The normalization of lying

We do not want to deny the existence of current leaders committed to the truth, but let us just say, as a starting point, that falsehood is not strange, not even exceptional, in the mouths of public figures that appear daily on our screens and in our newspapers. It is a global phenomenon: in the north and in the south, in large countries and in small nations, in democracies and in dictatorships, there are authorities who lie, and who lie blatantly. It is so common that it no longer shocks anyone.

Fortunately, there is no lack of more or less independent media that insist on highlighting the lack of integrity of public figures. It is already common, for instance, for the press to analyze the veracity of the statements of the participants in an electoral debate, once the debate has concluded. They inform us: "Candidate 1 distorted the reality in this statement; candidate 2 has no factual evidence to support what he said in response to candidate 3; the economic figures offered by candidate 3 are questionable.” They inform us, and nothing happens. This is the issue.

The real problem, we insist, is not that there are politicians who lie: the most serious matter is that the exercises to unmask their lies do not negatively affect their careers. The most serious matter is that they lie, we know it and nevertheless, we continue to vote for them, as if we did not care that men and women who are asking for our vote, or who already direct our governments, drop, here and there, inaccuracies, lies and slander. It seems, as we pointed out, that we have accepted that in the political game lies are inevitable.

Never let facts get in the way of a good story

Perhaps there is some truth in the idea that lies cannot be avoided, because the falsehood in which our leaders so easily fall is, in part, a consequence of the age in which we live. In our digitalized, accelerated and hyperconnected world, where nobody seems to have time to stop to examine the complexity of things, only simple messages work well. Our leaders have understood that their discourses must be direct, devoid of nuance, and they are forced to simplify very complex realities. Many times, therefore, the lie does not start as such: it starts as an attempt to reduce complicated problems to outlines that are easy to explain. To achieve this, one day an element of the problem is ignored ("there is no time to get into that today"); another day the aspect of the issue that we wish to highlight is magnified ("everything else is secondary"); another day the statement of an adversary is taken out of context; and very soon, after taking several steps in this direction (simplify, simplify, simplify) what is being communicated is nothing but a lie.

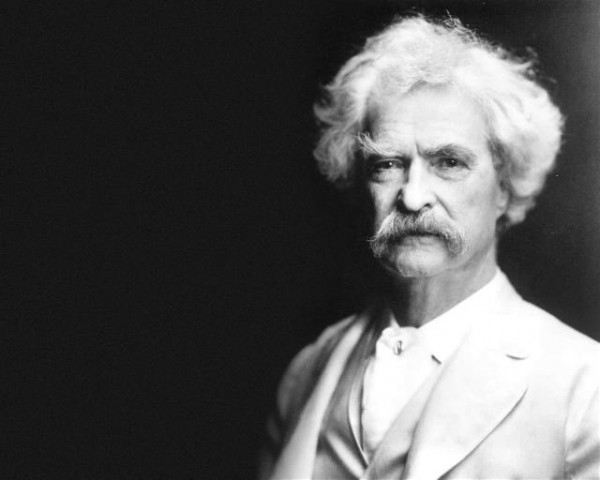

It would seem, in short, that our leaders have decided to follow the ironic saying attributed to Mark Twain: "Do not let the facts get in the way of a good story." The facts are a bother for those who seek the applause of a society that never has time to examine any issue calmly. That is what many understood, and it seems that more than one or two have turned the "advice" of Tom Sawyer’s author into their most sacred rule. With a tweet it is easier to explain a good story in black and white than to describe the gray tones and ambiguities of life. Of course, to make our history a good one, we will have to exclude uncomfortable and contradictory facts. Many politicians, invested in this logic, cease to be careful analysts of reality to become excellent storytellers: what matters is no longer rigorously examining the totality of the available data, its paradoxes and its ambivalences; what matters is to develop a coherent and attractive narrative that everyone can understand. Even if to achieve this we must discard some facts (those that would spoil the clarity of the story).

Mark Twain ironically described the mechanism of what today we call “post-truth”

We live immersed in a gigantic global information market. In this market, where the supply of messages is vast, those who believe they have something to say compete with each other tooth and nail to get the attention of a significant number of recipients. The struggle is unleashed to make sure that “my” message is heard by more people than yours; the fight is fierce to ensure that my opinion does not disappear in a few seconds, overwhelmed by the constant flood of other people's opinions. In this fight to get even some brief moments of relevance, the simple messages (the "good stories" that, to be so, must ignore the facts that would spoil them) are much more likely to survive than complex, nuanced messages. To say it somewhat harshly: if you want to be heard, lie.

Why do we allow them to lie to us?

What has been said so far may explain why the commitment of so many public figures to the truth is, at best, tenuous. Our leaders look for relevance, they are terrified to be thrown out of the spotlight, and they think that if they simplify their messages (and sooner or later that leads them to lie) they will be able to remain relevant. Yet, why does the tactic work? In other words, the question that remains to be answered is the one we asked ourselves at the beginning of this reflection: Why do we continue to vote for, listen to and applaud people who falsify the truth? Why do not we reject the liar? Why do we allow them to lie to us?

Although it is probable that there is no universal answer to this question, to think in the following direction seems interesting to us: perhaps we tolerate being lied to because we crave a home. We long with all our heart to have an ideological house, a community of thought and sensibilities that we may call "home" in which we may feel comfortable and safe. We want well-defined maps of the moral territory in which we move, and we want to recognize who is on our side. We need to know with whom we are family. This longing has a correlative fear: the terror of living without a home, of not having a side, of being what we might call "ideologically homeless.” It is this fear, combined with that longing, that leads us to tolerate the distortions of our leaders. In reality, what we expect from them is not a truthful and factually irreproachable discourse but a message that confirms our beliefs, certifying that we are on the right side, a message that ratifies our sensibilities, that corroborates what we already know. We do not want to question our leaders when they say half-truths or when they lie without blushing, because questioning them would push us to the periphery of the group and, from there, perhaps, to indigence and to becoming those ideological homeless we dread.

In short, we tolerate the lies of our leaders because they are ours. We let them lie because what matters is that they offer us the ideological house we long for.

Is it possible to correct this logic and recover the centrality of truth, so that facts can help us better understand the world in which we live and seek lasting solutions to our conflicts? We think so. To achieve this, the main thing for us to do is to lose the fear of living without a home, and to understand, somehow, that it is easier to see the stars from a clearing in the middle of the forest than from downtown. Freed from the fear of being left without an ideological house, we can dare to be a bit more critical of our leaders; we can dare to recognize what is reasonable in the position of our rivals; we can run the risk of examining the paradoxes, complexities and contradictions of each situation. And, we can stop sacrificing the facts in order to obtain a good story. Better yet: at last we will understand that the best story is the one that does not exclude any facts. Mark Twain, deep down, knew it very well.

Why do we allow them to lie to us?

What has been said so far may explain why the commitment of so many public figures to the truth is, at best, tenuous. Our leaders look for relevance, they are terrified to be thrown out of the spotlight, and they think that if they simplify their messages (and sooner or later that leads them to lie) they will be able to remain relevant. Yet, why does the tactic work? In other words, the question that remains to be answered is the one we asked ourselves at the beginning of this reflection: Why do we continue to vote for, listen to and applaud people who falsify the truth? Why do not we reject the liar? Why do we allow them to lie to us?

Although it is probable that there is no universal answer to this question, to think in the following direction seems interesting to us: perhaps we tolerate being lied to because we crave a home. We long with all our heart to have an ideological house, a community of thought and sensibilities that we may call "home" in which we may feel comfortable and safe. We want well-defined maps of the moral territory in which we move, and we want to recognize who is on our side. We need to know with whom we are family. This longing has a correlative fear: the terror of living without a home, of not having a side, of being what we might call "ideologically homeless.” It is this fear, combined with that longing, that leads us to tolerate the distortions of our leaders. In reality, what we expect from them is not a truthful and factually irreproachable discourse but a message that confirms our beliefs, certifying that we are on the right side, a message that ratifies our sensibilities, that corroborates what we already know. We do not want to question our leaders when they say half-truths or when they lie without blushing, because questioning them would push us to the periphery of the group and, from there, perhaps, to indigence and to becoming those ideological homeless we dread.

In short, we tolerate the lies of our leaders because they are ours. We let them lie because what matters is that they offer us the ideological house we long for.

Is it possible to correct this logic and recover the centrality of truth, so that facts can help us better understand the world in which we live and seek lasting solutions to our conflicts? We think so. To achieve this, the main thing for us to do is to lose the fear of living without a home, and to understand, somehow, that it is easier to see the stars from a clearing in the middle of the forest than from downtown. Freed from the fear of being left without an ideological house, we can dare to be a bit more critical of our leaders; we can dare to recognize what is reasonable in the position of our rivals; we can run the risk of examining the paradoxes, complexities and contradictions of each situation. And, we can stop sacrificing the facts in order to obtain a good story. Better yet: at last we will understand that the best story is the one that does not exclude any facts. Mark Twain, deep down, knew it very well.